FINDING a rare critter in the Australian bush can be a tricky business.

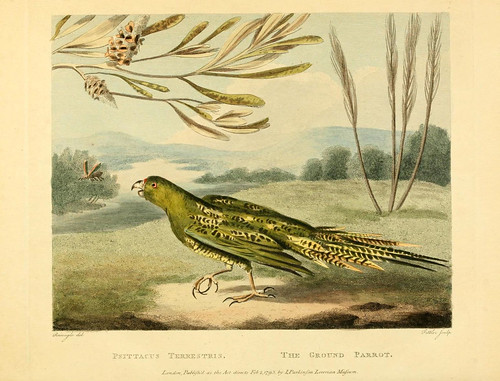

Very few people, bird watchers included, have ever seen the eastern ground parrot. Shy and elusive, the ground-dwelling birds are found in dense thickets of bush along the eastern seaboard, making their tunnels and nests in the undergrowth.

Similarly, the giant burrowing frog can be extremely hard to track down. Only a handful exist and they inhabit rocky ridges, and emerge only after rain.

But in a development that has potentially wide-ranging implications, scientists have developed technology that will allow them to map the numbers and location of some of Australia's most obscure wildlife.

The findings could help locate rare species or settle disputes between conservationists and developers about whether a threatened frog or bird exists on a particular site.

Elizabeth Tasker, from the NSW Department of Environment and Climate Change, is pioneering the use of a new machine known as the song meter. It is a passive listening device that can be left in the bush for months at a time and programmed to record at specific times of the day.

Software being developed at the University of Wollongong will allow signals from multiple song meters to be combined to help locate animals.

By placing several of the devices in an area, the data can be triangulated to identify an animal's exact location.

The Barren Grounds Nature Reserve on the Illawarra escarpment, south of Sydney, is one of the only places where the eastern ground parrots, which resemble giant green budgerigars, are found. It is also the site of the first pilot study.

The project, known as the Automated Acoustic Monitoring of Threatened Fauna study, is being funded by a charity, the Foundation for National Parks and Wildlife.

Ultimately the technology could have many different uses, including expanding the hunt for the mysterious night parrot of central Australia, which is feared extinct.

"Ornithologists have been searching for the night parrot for years, but it is just so rare the chance of being in the right place at the right time is very small," Dr Tasker said. "It may turn out not to be extinct; and these units are our best chance to find out whether it has survived."

Dr Tasker said the technology had great potential to be used across a range of species, particularly birds and frogs because of their distinctive calls. The even rarer eastern bristlebird, said to look and behave more like a bush rat than a bird, is likely to be the next bird researchers look for.

Leonie Gale, chief executive of the Foundation for National Parks and Wildlife, said the technology could revolutionise the way threatened species were monitored, located and protected. "Australia will lose many species in the next 30 years; this is a remote management tool for threatened species which could help stop that happening," she said.