In the Ecuador wilderness (guides Nelson, at the helm, and Paa), Charles Bergman sought the roots of the illegal animal trade (a blue-headed parrot chick). Photo: Charles BergmanTwo fire-red birds swooped screeching through the forest, flared their yellow and blue wings and alighted on the upright trunk of a dead palm tree. In the green shadows, the scarlet macaws were dazzling; they might as well have been shot from flamethrowers. One slipped into a hole in the tree, then popped its head out and touched beaks with its mate, whose long red tail pressed against the trunk. The birds eyed us suspiciously.

In the Ecuador wilderness (guides Nelson, at the helm, and Paa), Charles Bergman sought the roots of the illegal animal trade (a blue-headed parrot chick). Photo: Charles BergmanTwo fire-red birds swooped screeching through the forest, flared their yellow and blue wings and alighted on the upright trunk of a dead palm tree. In the green shadows, the scarlet macaws were dazzling; they might as well have been shot from flamethrowers. One slipped into a hole in the tree, then popped its head out and touched beaks with its mate, whose long red tail pressed against the trunk. The birds eyed us suspiciously.

As well they should have.

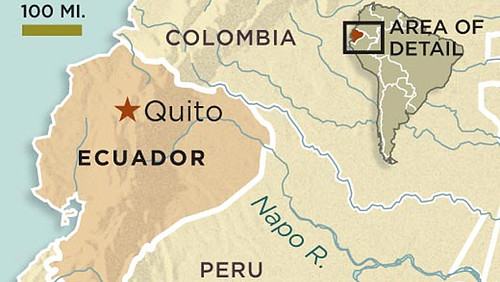

I was with hunters who wanted the macaws' chicks. We were in the Amazon Basin of northern Ecuador, where I had gone to learn more about wildlife trafficking in Latin America. I wanted to get to the source of the problem. I wanted to learn what its consequences were—for people and wildlife. These two macaws would serve as my lens.

Wildlife trafficking is thought to be the third most valuable illicit commerce in the world, after drugs and weapons, worth an estimated $10 billion a year, according to the U.S. State Department. Birds are the most common contraband; the State Department estimates that two million to five million wild birds, from hummingbirds to parrots to harpy eagles, are traded illegally worldwide every year. Millions of turtles, crocodiles, snakes and other reptiles are also trafficked, as well as mammals and insects.

Since 1973, the buying and selling of wildlife across borders has been regulated by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), whose purpose is to prevent such trade from threatening the survival of 5,000 animal and 28,000 plant species. CITES enforcement falls largely to individual countries, many of which impose additional regulations on wildlife trade. In the United States, the Wild Bird Conservation Act of 1992 outlawed the importation of most wild-caught birds. (Unless you're at a flea market on the southern border, any parrot you see for sale in the United States was almost certainly bred in captivity.) In 2007, the European Union banned the importation of all wild birds; Ecuador and all but a few other South American countries ban the commercial harvesting and export of wild-caught parrots.

"We do not lack laws against the trade," María Fernanda Espinosa, director of the International Union for Conservation of Nature in South America, said in her office in Quito, Ecuador's capital city. (She has since been named Ecuador's minister of culture and natural heritage.) "But there is a lack of resources, and that means it is not a conservation priority." In all of Ecuador, as few as nine police officers have been assigned to illegal trafficking.

Latin America is vulnerable to wildlife trafficking because of its extraordinary biodiversity. Ecuador—about the size of Colorado—has about 1,600 species of birds; the entire continental United States has about 900. Accurate data about the illegal trade in animals and plants are hard to come by. Brazil is the Latin American nation with the most comprehensive information; its Institute of Environment and Natural Resources cites estimates that at least 12 million wild animals are poached there each year.

Animals ripped from their habitat suffer, of course. They are smuggled in thermoses and nylon stockings, stuffed into toilet paper tubes, hair curlers and hubcaps. At one market in Ecuador, I was offered a parakeet. I asked the seller how I would get it on an airplane. "Give it vodka and put it in your pocket," he said. "It will be quiet." Conservationists say most captured wild animals die before reaching a buyer. In northwest Guyana, I saw 25 blue-and-yellow macaws—almost certainly smuggled from Venezuela—being carried from jungle to city in small, crowded cages. When I observed a police bust at a market in Belém, Brazil, one of the 38 birds confiscated was a barn owl crammed in a cardboard box hidden under furniture at the back of a market stall. At one rescue center outside Quito, I saw a turtle with two bullet holes in its carapace. Its owners had used it for target practice.

Animals stolen in Latin America often end up in the United States, Europe or Japan. But many never leave their native countries, being installed in hotels and restaurants or becoming household pets. In Latin America, keeping local animals—parrots, monkeys and turtles—is an old tradition. In parts of Brazil, tamed wild animals are called xerimbabos, which means "something beloved." In recent surveys, 30 percent of Brazilians and 25 percent of Costa Ricans said they had kept wild animals as pets.

In a raid at one market, environmental police in Belém, Brazil confiscated 38 birds being sold illegally and arrested traffickers. Photo: Charles BergmanHabitat loss is probably the main threat to New World tropical animals, says Carlos Drews, a biologist for the World Wildlife Fund in Costa Rica. "Wildlife trafficking and overexploitation are probably second." As one zoo director in Brazil told me, "There are no limits. You can buy whatever you want. Every species is for sale."

In a raid at one market, environmental police in Belém, Brazil confiscated 38 birds being sold illegally and arrested traffickers. Photo: Charles BergmanHabitat loss is probably the main threat to New World tropical animals, says Carlos Drews, a biologist for the World Wildlife Fund in Costa Rica. "Wildlife trafficking and overexploitation are probably second." As one zoo director in Brazil told me, "There are no limits. You can buy whatever you want. Every species is for sale."

My guides and I had been traveling by canoe down a small river in the Napo region of Ecuador when we found the scarlet macaws. We scrambled from the canoe and hustled through thick mud toward the tree, sinking at times to our knees. On a small rise, we quickly built a leafy blind out of tree branches. The macaws had left as we entered the jungle, and we waited behind the blind for them to return. We wanted to watch their comings and goings to see if they had chicks. The macaws returned to the nest right away. One announced itself with raucous "rraa-aar" screeches, then landed on the trunk, clinging sideways while it looked at the blind.

Like many parrot species, scarlet macaws (Ara macao) pair up in long-term relationships. They can live for decades. The birds eat fruit and nuts, nest high in trees, and raise one or two chicks at a time. Their range extends from Mexico to Peru, Bolivia and Brazil. We were lucky to find a pair nesting low enough to be easily visible.

Scarlet macaws are a study in primary colors—fiery red, cadmium yellow and dark blue. Yet each has distinctive markings. The red on the macaw at the nest shaded in places to flame orange, with blue tips to the yellow feathers on its wings. Small red feathers dotted its pale-skinned face, like freckles on a redhead. Apparently satisfied that there was no danger, the mate flew into the nest hole. The first bird left the tree, and the macaw in the hole peeked out at us.

"How much could this bird sell for?" I asked.

"Maybe $150 around here," said Fausto, the canoe driver. (I use my guides' first names to preserve their anonymity.)

I was surprised. I'd been offered many animals in my research on the wildlife trade, and $150 was about what I would have expected in Quito. It was more than what most people on this river make in a year.

Fausto, who came from another part of the country but had picked up the local language, made his living hauling cargo on rivers and hunting animals for meat. He had introduced me to Paa, a hunter from the Huaorani people, who had invited us to join him as he tried to catch a macaw. The Huaorani had fiercely maintained their independence through centuries of colonization; only when oil exploration reached this part of the Amazon in the 1960s and '70s did their culture begin to change. Many Huaorani still maintain traditional ways. They and other local indigenous people sometimes eat macaws.

Animals are central to the Huaorani, and almost as many pets as people live in Paa's community, from monkeys and macaws to turtles and tapirs. It is legal for the Huaorani and other indigenous peoples of Ecuador to capture animals from the jungle. The Huaorani domesticate the animals, or semi-domesticate them. What is illegal is to sell them. Paa said he wanted to catch the macaw chicks to make them pets. At a riverside bazaar, Bergman found an abundance of illicit goods, including turtle eggs and meat from 22 different species. Photo: Charles Bergman"Are you going to cut this tree down?" I asked Fausto.

At a riverside bazaar, Bergman found an abundance of illicit goods, including turtle eggs and meat from 22 different species. Photo: Charles Bergman"Are you going to cut this tree down?" I asked Fausto.

"It depends if there are babies or just eggs," he said.

Though the techniques for catching animals are as varied as human ingenuity, hunters often fell trees to capture chicks, which can be tamed to live with people. (Eggs are unlikely to yield chicks that live, and adults are too wild to domesticate.)

The macaw inside the nest eyed us for a time and then dropped out of sight into the cavity. The other macaw retreated to a roost above us in a tree, occasionally croaking to its mate.

Paa and Fausto spoke in Huaorani. Fausto translated: "There are no babies," he said. "They have eggs. We have to wait until the babies are bigger."

We agreed to return in several weeks, when the chicks would be near fledging.![]()

"But don't count on the nest still being here," Fausto said. "Someone else will take these birds. I know what happens on the river."

Psittacines—the parrot family, which includes parrots, parakeets and macaws—are among the most popular animals in the pet trade, legal and illegal. And no wonder. "What more could you ask for in a pet?" said Jamie Gilardi, director of the World Parrot Trust. Parrots are some of the most spectacular creatures in the world. "They seem as smart as a human companion and are incredibly engaging and endlessly fascinating," Gilardi said. "Humans find them fun to be around, and have done so for millennia." (At the same time, he cautions that parrots are also demanding pets that live for decades.) Indeed, archaeological studies have uncovered scarlet macaw feathers and bones dating from 1,000 years ago in Native American sites in New Mexico; the birds had been transported at least 700 miles.

International laws may be helping to reduce some parrot smuggling. The estimated number of parrots taken illegally from Mexico to the United States declined from 150,000 a year in the late 1980s to perhaps 9,400 now. But the toll on parrots of all kinds remains huge. In an analysis of studies done in 14 Latin American nations, biologists found that 30 percent of parrot nests had been poached; perhaps 400,000 to 800,000 parrot chicks were taken from nests every year. A Huaoroni woman stands in the background as her pet scarlet macaw takes center stage. “Scarlet macaws are a study in primary colors-fiery red, cadmium yellow and dark blue,” says Bergman. Photo: Charles BergmanMany experts say wild parrots can no longer sustain such losses. Of the 145 parrot species in the Americas, 46 are at risk of extinction. And the rarer the species, the more valuable it is to poachers—which only puts more pressure on the few remaining specimens. A single Lear's macaw, one of the coveted "blue macaws" from Brazil, can ultimately sell for $10,000 or more. The trade can send even apparently healthy species over the edge. Charles Munn, a parrot researcher at Tropical Nature, a Philadelphia-based conservation group that advocates ecotourism, told me, "If you shoot macaws for meat or feathers, or if you take the babies from the nest, you can wipe them out quickly. Poaching can get out of control quickly."

A Huaoroni woman stands in the background as her pet scarlet macaw takes center stage. “Scarlet macaws are a study in primary colors-fiery red, cadmium yellow and dark blue,” says Bergman. Photo: Charles BergmanMany experts say wild parrots can no longer sustain such losses. Of the 145 parrot species in the Americas, 46 are at risk of extinction. And the rarer the species, the more valuable it is to poachers—which only puts more pressure on the few remaining specimens. A single Lear's macaw, one of the coveted "blue macaws" from Brazil, can ultimately sell for $10,000 or more. The trade can send even apparently healthy species over the edge. Charles Munn, a parrot researcher at Tropical Nature, a Philadelphia-based conservation group that advocates ecotourism, told me, "If you shoot macaws for meat or feathers, or if you take the babies from the nest, you can wipe them out quickly. Poaching can get out of control quickly."

Several weeks after our first visit, we headed back to the scarlet macaw nest in a large canoe powered by a 25-horse-power motor. I had been thinking a lot about the macaws, wondering if I could persuade Paa not to cut down the tree.

It was just a couple of days before a feria, or market day, at a small town upstream from the nest. Canoes loaded with people and merchandise passed us; the passengers had been traveling for days, camping on sandbars. After reaching a dirt road built by the oil companies, they would hitchhike or walk another 15 miles to the village. Many canoes held animals. We stopped to visit with one boatload of 14 people, from elders to small babies. The driver offered to sell me an armadillo. It could be a pet or a meal, he said. He pulled a struggling baby armadillo, still pink, from a bag. He would let me have it for $20.

In the middle of the canoe were boxes of smoked meat. The charred hand of a monkey stuck out of one, fingers clenched. Indigenous people may legally hunt for subsistence purposes, but carne del monte, or wild meat, is illegal to sell without approval from the Ministry of Environment. Still, the meat is popular. At a market in the Ecuadoran Amazon Basin I saw for sale the meat of turtles, agoutis (a large rodent), armadillos and monkeys—all illegal. Other people on their way upriver to the feria carried peccaries (related to pigs), blue-headed parrots and parakeets. Selling them is just about the only way they had of making a few dollars.

The canoes carrying meat and animals for sale increased my worries about the scarlet macaws. Still, I had reason to hope the nest was intact. Paa said he had not heard anything about them. And two weeks earlier, I had heard through friends that Fausto had seen the birds at the nest on one of his trips downriver. Fausto was not with us this time. This canoe belonged to two young Huaorani brothers with English names, Nelson and Joel.

When we rounded the bend near the nest, the two macaws were sitting together on a branch. Their backs to us, they gleamed red in the morning sun. Their long tails waved and shimmered in the soft breeze. When they saw us, the birds screamed, lifted from their branch and disappeared into the dark forest. I was relieved to see them.

Then we saw the fresh footprints on the shore. We raced to the nest. The tree lay on the ground, smashed and wet. There were no chicks. All that remained were a few wet and mangled feathers near the nest hole.

We stood around the tree, speechless, as if by a coffin. Paa said he had not taken the chicks—someone else had. He shrugged. I was coming to realize, regardless of the laws in big cities, that capturing animals in the jungle is common. It's not the shadowy activity people might think; it's more like an open secret. The downed tree, to me, represented all the waste and destruction of this illicit trade, which destroys not only wild parrots but also the trees that serve as nest sites year after year. Thus trafficking harms future generations, too.

We did not know whether the babies survived the crash of the tree onto the ground. (A recent study in Peru found that 48 percent of all blue-and-yellow macaws die when their trees are felled.) Even after the nest had been robbed, the parent macaws had stayed by the downed tree, the image of fidelity and loss. Wildlife trafficking is thought to be the third most valuable illicit commerce in the world, after drugs and weapons, worth an estimated $10 billion a year, according to the U.S. State Department. Photo: Guilbert Gates"Who do you think did this?" I asked no one in particular.

Wildlife trafficking is thought to be the third most valuable illicit commerce in the world, after drugs and weapons, worth an estimated $10 billion a year, according to the U.S. State Department. Photo: Guilbert Gates"Who do you think did this?" I asked no one in particular.

Nelson said: "Three or four days ago, Fausto was seen coming up the river. He had three scarlet macaw chicks in his canoe."

Could it have been Fausto, who warned me that he did not think this nest would survive? It had not occurred to me that he would poach these macaws, and it felt like a betrayal. The next day, on the river, we would ask him ourselves.

We were having lunch on a sandbar when we heard another canoe motoring upriver—Fausto, returning home. He had been hunting. His canoe held two live turtles and a dead guan, a turkey-like bird.

We asked him if he had taken the macaw chicks. He denied it.

"But I know who did it," he said. "They told me there were only eggs still in the nest. No chicks."

We asked him about the three scarlet macaw babies he had in his canoe just a few days earlier.

"Those were from another nest farther downriver," he said. He said he had cut down another tree with crimson-fronted macaws, near his house, but the babies were already fledged and flew out of the nest hole as the tree crashed to the ground.

His story seemed garbled and doubtful. In any event, it was clear that he was poaching animals. I had traveled with a trafficker for more than a week without realizing it.

As we rode back up the river, I asked the Huaorani men if they worried that overhunting would mean their wildlife would disappear. "We have to put the brakes on," Nelson said, adding that they had to travel farther and farther just to find animals. "We see the animals disappearing. We have to raise consciousness. We want to be the protectors of wildlife."

In his early 20s, Nelson may speak for a new generation in the Amazon Basin of Ecuador. A few others I spoke with shared his view. Some are hoping to turn to tourism as an alternative to poaching. The Napo Wildlife Center in Ecuador, for instance, employs Quichua people as expert guides for tourists. Anti-poaching initiatives are trying to raise awareness about wildlife and provide incentives to protect it.

Still, people are poor, and they continue to see wildlife as a resource to earn money. During one nesting season, we had identified five active nests of macaws and parrots, including the scarlet macaws, two pairs of chestnut-fronted macaws, one pair of blue-headed parrots and one pair of black-headed parrots. As we journeyed up and down the river, we watched for the nest trees. Every one of them had been cut down. The parents had vanished. Here and in many places, trafficking is creating a strange world, a forest without its creatures—a naked forest.

Charles Bergman has written about jaguars and monkeys for Smithsonian and is writing a book about the wild animal trade.