A budgie relays information from its eyes on each side of the head and compares them to motion, to navigate. Scientists have found that budgies can be tricked by optical illusions because of how they use vision to navigate.

A budgie relays information from its eyes on each side of the head and compares them to motion, to navigate. Scientists have found that budgies can be tricked by optical illusions because of how they use vision to navigate.

IN SPITE OF THE occasional thump into a clear window, birds are remarkably adept at flying through narrow passages at high speeds and new research has revealed just how they do it.

A recent Australian study has found that budgies successfully navigate tricky spaces by using some simple visual cues that help them gauge how fast they're moving.

The birds use a similar navigation technique to that used by honeybees. Both creatures have eyes on either side of their head, which means they cannot calculate distances between objects (known as depth perception) as well as can humans or other animals with forward-facing eyes.

Without much stereo vision, budgies have a hard time working out how far way objects are.

Instead, the birds compare how fast their surroundings appear to be rushing past in each eye to make sure their flight path is smooth and unobstructed.

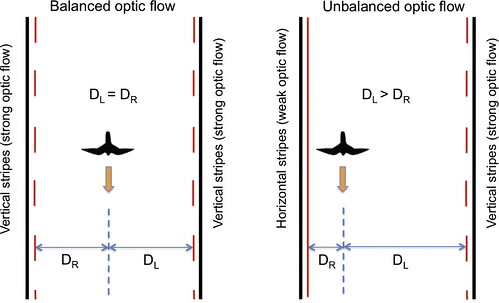

"They position themselves…in such a way that the speed or the motion of [what they see] on each side is about the same," says Professor Mandyam Srinivasan (known as Srini), a study author and visual neuroscientist at the Queensland Brain Institute and the ARC Centre of Excellence in Vision Science.

Using this visual feedback to navigate is faster and less complicated than other methods. Budgies do not have to figure out how far they are from an object; they simply try to position themselves at the centre of a tight passageway and keep the world rushing past at about the same speed on both sides.

Bird flight mystery revealed

In the recent study, the researchers used optical illusions to alter with the birds' sense of motion. They lined the walls of a narrow corridor with vertical stripes, horizontal stripes, or no pattern at all, and tracked the birds' flight paths through the corridor in three dimensions using a series of high-speed stereo video cameras.

Birds regulate flight speed by monitoring induced image motion (optic flow) As it turns out, budgies reacted strongly to changes in decor.

Birds regulate flight speed by monitoring induced image motion (optic flow) As it turns out, budgies reacted strongly to changes in decor.

"If you have vertical stripes on the left side and horizontal stripes on the right side, the birds fly a lot closer to the horizontal striped wall," Srini says. "They almost graze that wall with their wings."

In essence, the birds have difficulty flying straight in situations where the landscape on one side does not look like it is moving. Vertical stripes, which lie perpendicular to the flight path, give the birds a sense of how fast they are flying, while horizontal stripes or blank walls trick the birds into thinking they are not moving very fast at all.

From birds to planes

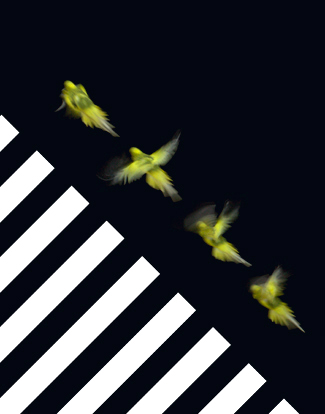

This image above is an abstract rendition of a sequence of images illustrating the flight of a budgerigar through a tunnel. The walls are decorated with various visual patterns which researchers used to investigate visual guidance of bird flight. (Credit: Dr. Ingo Schiffner)The research is the first of its kind to study how birds navigate using visual cues. While the findings only apply to budgies for now, it is possible that birds and other flying animals use similar navigation techniques.

This image above is an abstract rendition of a sequence of images illustrating the flight of a budgerigar through a tunnel. The walls are decorated with various visual patterns which researchers used to investigate visual guidance of bird flight. (Credit: Dr. Ingo Schiffner)The research is the first of its kind to study how birds navigate using visual cues. While the findings only apply to budgies for now, it is possible that birds and other flying animals use similar navigation techniques.

"The paper is very interesting," says Professor Ken Chang, who studies animal behaviour at Macquarie University in Sydney. "It makes important contributions considering the evolution of how things work."

Ken says the group's findings demonstrate how the evolution of a given species can be driven by the laws of physics, and how visual navigation may be an evolutionary advantage as it requires less energy than other methods.

Both Ken and Srini believe these results may have broader implications for flying creatures—including those of our own creation.

"We are putting some of the ideas…into vision systems for aircraft," he says. [Srini's] research team is currently designing planes that use the same navigation method to fly without human assistance.

Birds may also benefit from the research. Srini hopes his findings will help make glass-filled cities and wind farms a little more bird-friendly.

"Maybe there are ways to project moving patterns or even design appropriate stationary patterns that could minimise risk to birds," Srini says.