In Qatar, Ryan Watson, blue macaw coordinartor for al-Wabra Wildlife Preservation, watches a young Spix's macaw named Jewel in the facility's nursery. There are just 76 Spix's macaws left on Earth, all in captivity. Lindsay Borthwick / For The Washington Post

In Qatar, Ryan Watson, blue macaw coordinartor for al-Wabra Wildlife Preservation, watches a young Spix's macaw named Jewel in the facility's nursery. There are just 76 Spix's macaws left on Earth, all in captivity. Lindsay Borthwick / For The Washington Post

AL-SHEEHANIYA, Qatar — Cobalt-plumed and flapping, Jewel, a young Spix’s macaw, hops into a plastic bowl. She’s well trained in the routine. Her handler, Ryan Watson, sets the bowl on a scale. He’s pleased. The 4-month-old parrot is growing.

If Jewel continues to thrive, Watson will soon move her and a companion — a second young macaw shrieking at the far end of the pair’s long enclosure — to a larger aviary, where they will flock with others of their kind.

Though the distance of the move will be short, it has far-reaching implications: It will foster fledgling hope that this rarest of parrots can be saved. Just 76 of the handsome blue birds — endemic to northern Brazil but unseen there in 11 years — are known to exist, all in captivity. Watson was hired by a member of Qatar’s royal family, Sheik Saoud bin Mohammed bin Ali al-Thani, to rescue the species from the edge of extinction and send it soaring back into the Brazilian jungle.

It’s an audacious plan in an improbable locale, this oil-and-gas-rich kingdom on the Arabian Peninsula. With no signs marking it in the flat, arid landscape, a fenced private wildlife compound extends across 1.6 square miles about 20 miles west of the capital, Doha.

A young Spinx's Macaw named Jewel hangs from her enclosure at al-Wabra Wildlife Preservation. Lindsay BorthwickAl-Wabra Wildlife Preservation began as a private menagerie with a questionable past. But it has been transformed into an intensive conservation operation. The desert preserve is owned by Saoud, a keen collector of rare beauties, including Islamic antiquities for his home and, here, slender gazelles, brilliant birds of paradise, Arabian sand cats and majestic macaws.

A young Spinx's Macaw named Jewel hangs from her enclosure at al-Wabra Wildlife Preservation. Lindsay BorthwickAl-Wabra Wildlife Preservation began as a private menagerie with a questionable past. But it has been transformed into an intensive conservation operation. The desert preserve is owned by Saoud, a keen collector of rare beauties, including Islamic antiquities for his home and, here, slender gazelles, brilliant birds of paradise, Arabian sand cats and majestic macaws.

Aviaries, breeding enclosures, antelope runs and primate houses shelter about 2,000 animals from 90 rare and endangered species. A staff of 200 — including four veterinarians and five biologists — maintains the compound and cares for the animals, kept in 480 enclosures.

Private menageries are common in the region, said Watson, a 33-year-old Australian who heads the blue macaw breeding program. And the preserve once fit that unflattering description. “We make no secret that the sheik collected animals from black-market dealers, from the wild, from wherever he could,” Watson said. Before 2001, when Qatar signed a key international treaty, known as Cites, restricting trade in endangered animals, it was not illegal to import rare animals.

Which is exactly what Saoud did after he inherited the compound. But a 1999 incident triggered a conservation awakening. After Saoud flew rare Beira antelopes out of East Africa, local elders accused him of poaching, according to a BBC report that year.

“That’s the last time there’s been any of that kind of activity,” Watson said. “We’ve made the transition from hobby farm to the breeding center we are now.”

Jewel gets weighed in the nursery at al-Wabra Wildlife Preservation. Lindsay Borthwick / FOR THE WASHINGTON POSTThe preserve breeds its animals, does exchanges with other facilities and, on the rare occasion, rescues animals, as it did in 2006, adopting four South American golden-headed tamarins found dehydrated on the back of a truck in Qatar. That was the last new species added to the collection.

Jewel gets weighed in the nursery at al-Wabra Wildlife Preservation. Lindsay Borthwick / FOR THE WASHINGTON POSTThe preserve breeds its animals, does exchanges with other facilities and, on the rare occasion, rescues animals, as it did in 2006, adopting four South American golden-headed tamarins found dehydrated on the back of a truck in Qatar. That was the last new species added to the collection.

The turnabout has garnered allies in the conservation community, and the staff regularly collaborates with international experts. They discuss their successes as well as their failures.

Such as the half-million dollars the sheik paid to protect the dibatag antelope of Ethiopia. The money was, as Watson puts it, “flushed down the toilet” when a newly built compound was raided there. On the preserve, tuberculosis ripped through a herd of Beira antelopes, dropping the population from 60 to 19. (Although a bounding 10-week-old Beira in a pen suggests the worst of the outbreak is over.)

Since arriving at al-Wabra preserve in 2005, Watson has overseen the hatching of 24 Spix’s macaws. Combined with birds bought from a commercial breeder in the Philippines and a collector in Switzerland, the facility shelters 55 Spix’s macaws, nearly 75 percent of the world’s known population.

“The bottom line is, the future of the species now rests in the hands of the sheik,” said Russell Mittermeier, president of Conservation International. Or, perhaps more accurately, in the hands of Watson.

Genetic bottleneck

But the going is tough. “The birds don’t do very well in captivity,” Watson said, leading visitors past an antelope run and toward an aviary. Many of the older birds — they can live for 30 years or longer — suffer from weak kidneys, the result of dehydration when they were smuggled from Brazil to private collectors decades ago.

A more worrisome problem is the genetic bottleneck caused by extreme inbreeding. All but four of the surviving birds descended from a brother-sister pair kept by the Swiss breeder. As a result, only 2 percent of eggs laid by second-generation captive females hatch. Tests allow breeders to select pairs with the greatest genetic diversity, but those couples don’t always produce eggs.

And for unknown reasons, the hatchlings that do emerge skew heavily female. Because Spix’s macaws form strong pair bonds, that means a gender balance will ultimately be required for the species to thrive.

The struggle for survival intensified in 2004, when the staff learned that many of their parrots harbored an infectious wasting condition called proventricular dilatation disease. A scourge of parrot breeders for decades, PDD ravaged al-Wabra’s collection.

The picture brightened only after scientists at the University of California at San Francisco identified the virus, and Watson and his team began to isolate infected individuals. The result: No new infections in three years.

Now the flock is growing again, creeping up from 51 individuals in 2007 to 55 today.

A 50-50 chance

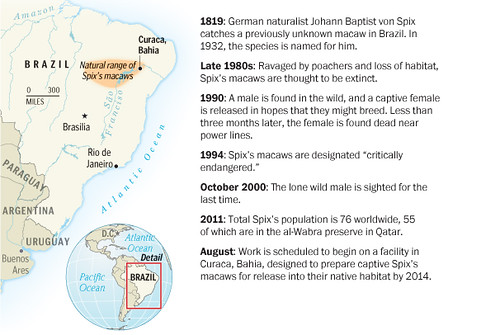

Spix’s macaws no longer roam their natural territory in northeastern Brazil, but conservationists hope that a new center will reintroduce the rare blue parrots to their homeland. Sources: International Union for Conservation of Nature, NatureServe, Al-Wabra Wildlife Preservation. Bonnie Berkowitz and Rob Cady/The Washington Post.Nine of the macaws live in one aviary. A keeper opens a window leading from the birds’ roosting room into the fern- and tree-filled space. One, two, three, four, five blue darts shoot out, spread their wings and soar up to perch on a high branch. Looking down at visitors, they trill and call. These instinctual warning sounds will serve them well in the forests of Brazil, their ultimate destination.

Spix’s macaws no longer roam their natural territory in northeastern Brazil, but conservationists hope that a new center will reintroduce the rare blue parrots to their homeland. Sources: International Union for Conservation of Nature, NatureServe, Al-Wabra Wildlife Preservation. Bonnie Berkowitz and Rob Cady/The Washington Post.Nine of the macaws live in one aviary. A keeper opens a window leading from the birds’ roosting room into the fern- and tree-filled space. One, two, three, four, five blue darts shoot out, spread their wings and soar up to perch on a high branch. Looking down at visitors, they trill and call. These instinctual warning sounds will serve them well in the forests of Brazil, their ultimate destination.

First, though, Watson and his wife, Monalyssa Camandaroba Watson — a macaw expert from Brazil — need to smooth the way. In August, they plan to move to a 6,000-acre farm bought by Saoud in northern Brazil. There, they will build a hatchery, a nursery and an aviary.

Following a step-by-step plan, they hope to introduce captive-bred macaws into the wild. Initially, they will let the birds out only in the evening, drawing them back to the aviary with food and water. Slowly, Ryan Watson hopes, the birds will learn to eat wild food and avoid predation.

The Watsons will test the process with a more abundant Brazilian species, the Illiger’s macaw. If captive birds of that species adapt well, within three years, young Spix’s macaws will be flown home.

“It’s 50-50,” Watson said, assessing the macaws’ odds of survival. He has heard all the criticisms: There aren’t enough birds for a reintroduction plan. There’s too little genetic diversity. Poachers will pluck them out of the trees.

But it’s time to try. “If they’re not out in the wild, what’s the point?” Watson asked, squinting at a setting desert sun. “Wild animals belong in the wild. Otherwise, what we’re doing is not conservation.”