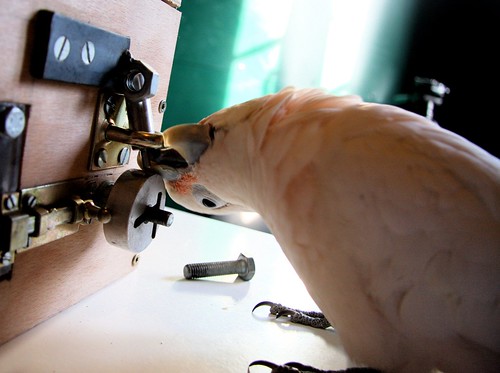

A cockatoo called Muppet solving a bolt-type lock. (Photo: Alice Auersperg)A species of Indonesian parrot can solve complex mechanical problems that involve undoing a series of locks one after another, revealing new depths to physical intelligence in birds.

A cockatoo called Muppet solving a bolt-type lock. (Photo: Alice Auersperg)A species of Indonesian parrot can solve complex mechanical problems that involve undoing a series of locks one after another, revealing new depths to physical intelligence in birds.

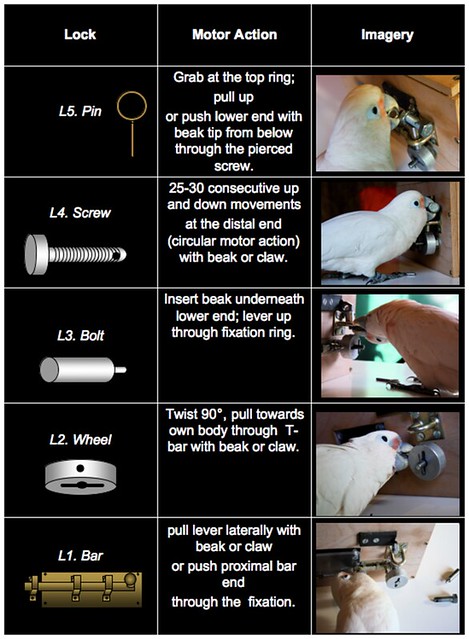

A team of scientists from Oxford University, the University of Vienna and the Max Planck Institute report in PLOS ONE a study in which ten untrained Goffin's cockatoos faced a puzzle box showing food (a nut) behind a transparent door secured by a series of five different interlocking devices, each one jamming the next along in the series.

To retrieve the nut the birds had to first remove a pin, then a screw, then a bolt, then turn a wheel 90 degrees, and then shift a latch sideways. One bird, called Pipin, cracked the problem unassisted in less than two hours, and several others did it after being helped either by being presented with the series of locks incrementally or being allowed to watch a skilled partner doing it.

The scientists were interested in the birds’ progress towards the solution, and on what they knew once they had solved the full task.

The team found that the birds worked determinedly to overcome one obstacle after another even though they were only rewarded with the nut once they had solved all five devices. The scientists suggest that the birds seemed to progress as if they employed a 'cognitive ratchet' process: once they discovered how to solve one lock they rarely had any difficulties with the same device again. This, the scientists argue, is consistent with the birds having a representation of the goal they were pursuing.

After the cockatoos mastered the entire sequence the scientists investigated whether the birds had learnt how to repeat a sequence of actions or instead responded to the effect of each lock.

Dr Alice Auersperg, who led the study at the Goffin Laboratory at Vienna University, said: 'After they had solved the initial problem, we confronted six subjects with so-called 'transfer tasks' in which some locks were re-ordered, removed, or made non-functional. Statistical analysis showed that they reacted to the changes with immediate sensitivity to the novel situation.'

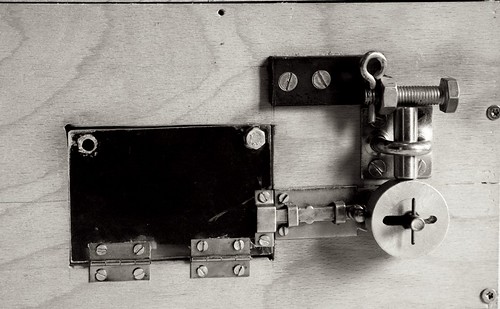

The puzzle box lock mechanism (original configuration)Professor Alex Kacelnik of Oxford University's Department of Zoology, a co-author of the study, said: 'We cannot prove that the birds understand the physical structure of the problem as an adult human would, but we can infer from their behaviour that they are sensitive to how objects act on each other, and that they can learn to progress towards a distant goal without being rewarded step by step.'

The puzzle box lock mechanism (original configuration)Professor Alex Kacelnik of Oxford University's Department of Zoology, a co-author of the study, said: 'We cannot prove that the birds understand the physical structure of the problem as an adult human would, but we can infer from their behaviour that they are sensitive to how objects act on each other, and that they can learn to progress towards a distant goal without being rewarded step by step.'

Dr Auguste von Bayern, another co-author from Oxford University, said: 'The birds' sudden and often errorless improvement and response to changes indicates pronounced behavioural plasticity and practical memory. We believe that they are aided by species characteristics such as intense curiosity, tactile exploration techniques and persistence: cockatoos explore surrounding objects with their bill, tongue and feet. A purely visual explorer may have never detected that they could move the locks.'

Professor Kacelnik said: 'It would be too easy to say that the cockatoos understand the problem, but this claim will only be justified when we can reproduce the details of the animals' response to a large battery of novel physical problems.'

A report of the research, entitled 'Explorative learning and functional inferences on a five-step means-means-end problem in Goffin's cockatoos (Cacatua goffini)' is to published in this week’s PLOS ONE.