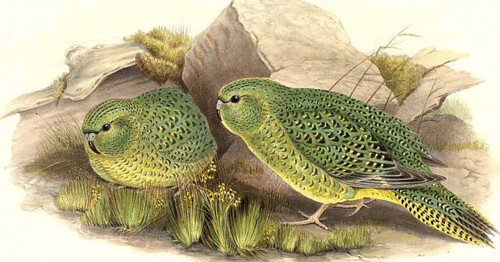

The mysterious night parrot. (Credit: John Gould) An ornithologist has captured the first photos and some intriguing insights into Australia’s most elusive bird.

The mysterious night parrot. (Credit: John Gould) An ornithologist has captured the first photos and some intriguing insights into Australia’s most elusive bird.

FIFTEEN long years of scouring the remote outback of central Australia has paid off for a Queensland ornithologist who has collected the first photographs and video footage of the night parrot, the nation’s most elusive bird.

At a briefing held on Wednesday at the Queensland Museum, in Brisbane, John Young explained how he had spent many years searching spinifex clumps, gibber plains, caves, gullies, salt lakes and countless other habitats across Australia’s arid heart, looking for what has been labelled the holy grail of Australian birding.

“I know now from walking through their habitat that they are the most secretive thing I have ever seen in my life and certainly the hardest [species] I’ve ever worked on,” he said.

The night parrot revealed

The night parrot (Pezoporus occidentals) was described in 1861 and the last live specimen was caught in Western Australia in 1912, but since then, save for a smattering of sightings and several dead specimens, it has barely been seen again.

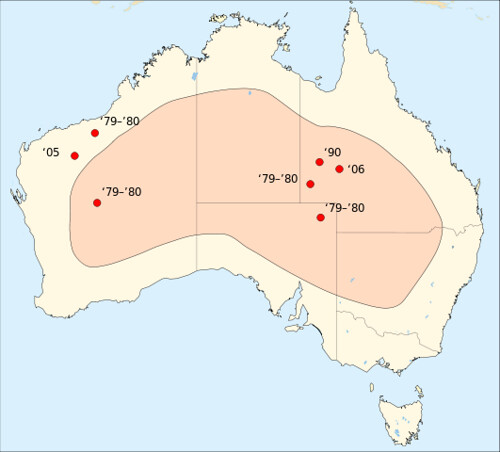

The most recent unconfirmed sighting was in the Pilbara in 2005, and a dead female was found in Queensland's Diamantina National Park in 2006.

On Saturday it was reported that John had captured the first photographs of the species (see Tweets in the night, a flash of green: is this our most elusive bird?), but it wasn’t until today that a wider selection of photos and a video footage were presented to scientists.

“John has clearly spent many cold nights out there in central Australia sitting and waiting for this bird. It’s a fantastic effort and he has been rewarded with phenomenal footage and images,” said Dr Max Tischler an expert on desert ecology with Bush Heritage Australia.

“The night parrot is a real enigma. It’s got this myth about it – this bird where only a handful of specimens were collected in the late 1800s and then it largely disappeared. A few dead specimens but no footage and no photos, nothing like that,” he told Australian Geographic. “Anyone who’s been out in the desert has always kept their ears and eyes one hoping one might scurry across their paths.”

Cracked the parrot problem

“John has cracked the problem of how to find and how to hang on to them,” said Dr Leo Joseph, director of the CSIRO Australian National Wildlife Collection in Canberra, who congratulated him on his achievement. “Nobody has been able to reliably report finding a night parrot before now and the problem has been getting back to the same spot and relocating them.”

To the collective gasps and murmurs of crowd of ornithology enthusiasts and experts, John revealed a number of close-up images and a six seconds of video footage, which appeared to show the bird hopping along the ground, kangaroo-style – a behaviour not well known in other species of parrot.

In a number of years studying birds at an undisclosed site in far western Queensland he says he has learnt much about the biology of the species. “You can’t pin something down until you know it really well,” John told the gathering.

One insight is that they live very deep within clumps of spinifex and only emerge at night, not dawn and dusk as was previously thought.

John says that – based on the shape of the beak and from samples of guano collected – he also doesn’t believe the species is mostly a seed eater as had been supposed. From fragments of insects, such as wing cases, found in the birds’ waste and below roosts found deep in clumps of spinifex, he estimates that “at least a third of its diet is insects.”

Succulent plants are also thought to form part of its diet and may be an important water source.

Unusual biology of the bird

John says there may be several breeding pairs at the site and one of the females may have been brooding a nest of young based on the calls he has heard. The location of the site is tightly under wraps at the moment and has yet to be revealed to other experts or the authorities. An air of secrecy surrounded much of the information released at the briefing today.

Photographs were not available for online distribution at all at this stage and audio clips of the call were not released either, to prevent birders from using them to attract night parrots and potentially disturbing the secretive birds.

John recounted the story of how late one night in 2009 in central Australia he awoke to the distant sound of what seemed to him to be an unusual kind of parrot call he had never heard before. He attempted to copy the whistles himself and was able to attract two birds in within about 20m which he was convinced were night parrots.

“We got the first call ever of the bird that night,” says John who recorded the song and then subsequently used it to attract night parrots in for study and to capture the photographs and video footage that he got on 26 May this year.

He described how on that night the recording elicited an aggressive and territorial response in a male bird which approached close enough to be photographed.

“He was tapping the ground...banging his feet on the ground, chucking stones everywhere and when he eventually came around the front, he was puffed up like an echidna, double the size. I’ve never seen a parrot do that in my life,” John said.

“The more I played it the more aggressive he becomes. He started to scream like a budgerigar... Making really loud budgerigar-type noises and I heard something that night I’ll probably never hear again, because I won’t be playing a call in their territory again ever.”

Historic night parrot distribution (pale red) and reported sightings since 1979 (red dots). (Credit: KinvdLinde/Wikipedia)

Historic night parrot distribution (pale red) and reported sightings since 1979 (red dots). (Credit: KinvdLinde/Wikipedia)

Courting controversy

Some of the features of the birds’ biology revealed by John Young “explains why it has taken so long to find it,” says Max Tischler. “It’s ground dwelling and lives in very dense vegetation and if it’s very shy and doesn’t respond readily to calls then that makes it very difficult to detect. Against it’s just one of the really puzzling aspects of this bird.”

Controversy has courted John in the past , and claims he has made regarding rare bird sightings have been challenged (see: Tweets in the night, a flash of green: is this our most elusive bird?), but this time he made sure to have a solid body of evidence before making the discovery public. “I made some mistakes in the past, but I bloody well didn’t this time because I took the [memory] card out and locked it in the bank,” he said.

Experts are now considering how best to protect the western Queensland site and control predators such as cats and foxes which could threaten the survival of what is undoubtedly a thinly distributed species.