Annie Hawkinson looks down from a macaw nest.

Annie Hawkinson looks down from a macaw nest. Veterinarian Zoltan Szabo measures one of the chicks.

Veterinarian Zoltan Szabo measures one of the chicks. The team is collecting all sorts of measurements that will tell them how much, and how fast, the chicks are growing.

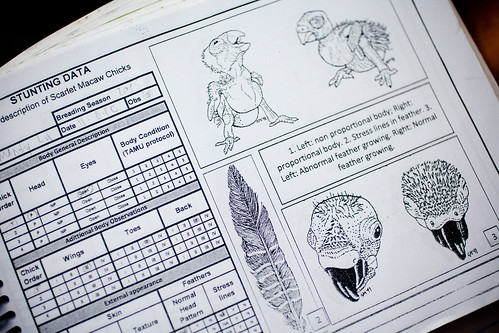

The team is collecting all sorts of measurements that will tell them how much, and how fast, the chicks are growing. Veterinarian Zoltan Szabo sets up a makeshift desk with various tools needed to measure the health and growth of the chicks.

Veterinarian Zoltan Szabo sets up a makeshift desk with various tools needed to measure the health and growth of the chicks. Volunteer researcher Kathrin Meyer uses binoculars to observe one of the macaw nests from the ground.

Volunteer researcher Kathrin Meyer uses binoculars to observe one of the macaw nests from the ground. Wild macaws fly overhead in the rainforest. Scientists have attached satellite tracking collars to some of the area's macaws, which turned out to regularly fly to Bolivia and back.

Wild macaws fly overhead in the rainforest. Scientists have attached satellite tracking collars to some of the area's macaws, which turned out to regularly fly to Bolivia and back. Donald Brightsmith looks out from the thatched roof that covers the research facility. He started coming here in 1999 to study the local macaw population.

Donald Brightsmith looks out from the thatched roof that covers the research facility. He started coming here in 1999 to study the local macaw population. Annie Hawkinson cleans out her gear from her morning expedition, which began before 5:30 a.m.

Annie Hawkinson cleans out her gear from her morning expedition, which began before 5:30 a.m. Macaws have formidable beaks and talons, and meeting those with your bare hands can be treacherous. So, scientists sometimes use these stuffed gloves when reaching into macaw nests.

Macaws have formidable beaks and talons, and meeting those with your bare hands can be treacherous. So, scientists sometimes use these stuffed gloves when reaching into macaw nests. Annie Hawkinson naps in a hammock in the researcher living quarters of TRC.

Annie Hawkinson naps in a hammock in the researcher living quarters of TRC. Researchers shout down to the ground floor from their elevated live/work space at TRC.

Researchers shout down to the ground floor from their elevated live/work space at TRC. Researchers' rooms are shared, and beds are draped with mosquito nets. Volunteers and scientists stay at TRC for varying lengths of time, from as short as a few weeks to six months.

Researchers' rooms are shared, and beds are draped with mosquito nets. Volunteers and scientists stay at TRC for varying lengths of time, from as short as a few weeks to six months. Brightsmith and his 16-month-old daughter, Amanda Lucile, in the live/work space set up for the researchers at TRC. One of the newest nests around the lodge, Mandy Lu, is named after his daughter.TAMBOPATA, Peru — It’s 6:15 a.m, and Annie Hawkinson is 120 feet off the ground, peering into a nest box lashed to an ironwood tree. She throws a towel over the female scarlet macaw inside, then reaches in and grabs one of the two chicks. Mama macaw squawks and shuffles out from beneath the towel. Hawkinson repeats the maneuver and grabs the second chick, then lowers the ungainly pair to the ground in a padded bucket. She waits near the nest, where the macaw is now preening and appears unperturbed.

Brightsmith and his 16-month-old daughter, Amanda Lucile, in the live/work space set up for the researchers at TRC. One of the newest nests around the lodge, Mandy Lu, is named after his daughter.TAMBOPATA, Peru — It’s 6:15 a.m, and Annie Hawkinson is 120 feet off the ground, peering into a nest box lashed to an ironwood tree. She throws a towel over the female scarlet macaw inside, then reaches in and grabs one of the two chicks. Mama macaw squawks and shuffles out from beneath the towel. Hawkinson repeats the maneuver and grabs the second chick, then lowers the ungainly pair to the ground in a padded bucket. She waits near the nest, where the macaw is now preening and appears unperturbed.

Well, the brilliant adult one of them will become.

Though macaw parents lay as many as four eggs, it’s the rare pair that raises more than one chick. Observations suggest that this outcome is one of choice, rather than resource limitation. So far, the reasons why are still a mystery. This parenting strategy seems to be unusual even among birds, which often lay extra eggs and then distribute limited resources among chicks with brutal efficiency.

When Szabo weighs these two little birds (before returning them to their nest), evidence of the second chick’s impending demise is already apparent: At only 90 grams, the tiny bird is about half the weight of its sibling. Usually, the chicks destined to die don’t survive for more than three weeks. Earlier this morning, Szabo and Hawkinson — volunteers with the Tambopata Macaw Project — had visited a new nest named Mandy Lu (after one researcher’s daughter). The nest contained a single, plump, two-week-old chick — its two siblings had already died.

The truth is that macaw chick mortality does not appear to be the accidental or inevitable result of scarce resources.

“This is death by neglect,” said ornithologist Donald Brightsmith of Texas A&M University. “Complete and utter neglect.”

Brightsmith has been coming to the Tambopata Research Center since 1999 to study the local macaw population. Now, he’s director of the Tambopata Macaw Project, which kicked off in 1989. Over the last quarter-century, data gathered by the project’s scientists and volunteers have revealed important information about these beautiful, endangered birds — including the local macaws’ unusual habit of eating clay, the places the birds fly to throughout the region, and their natural history and reproductive strategies.

That includes studying what some might consider to be the antithesis of good parenting.

“Why do the parents not try to fledge three or four chicks?” Brightsmith asked. “That’s a complicated one that I don’t really know the answer to.”

For starters, it seems the birds lay multiple eggs because chances are, they won’t all hatch. Laying more eggs means there’s a better chance of at least one chick being reared to fledging. “The egg is valuable, only because hatching success is fairly low,” Brightsmith explains. “But if that third chick hatches, it’s not valuable. The parents are just not interested in it.”

Observations based on footage captured by in-nest video cameras, placed by Texas A&M graduate student Gabriela Vigo, and the kind of work Hawkinson and Szabo are doing, suggest that macaw parents pay attention to the order in which their chicks hatch. A first-born chick’s chances of survival vastly outnumber those of its subsequent siblings. Odds are about even for the second-born. The third? More than 90 percent of them don’t make it. A fourth chick has about zero chance of surviving. Once the chosen chick is selected, the macaw parents will preferentially feed it – sometimes until it is beyond stuffed – while ignoring the others. And not just in terms of food. “Mom won’t even brood them,” Brightsmith said. “She’s not even sharing body heat with them, let alone food.”

Szabo records information about the chick from the Mandy Lu nest. Photo: Ariel Zambelich/WIREDIt’s not always that simple, though. Sometimes mom and dad disagree about which chicks to feed. And, there are the rare exceptions in which parents have raised as many as three chicks at once. That’s not easy. Macaw parenting is intense and the amount of parental investment required is huge. It extends beyond the three-month period when the chicks are in the nest: Once fledged, chicks can stay near their parents for as long as a year, learning how to forage for food and defend themselves.

Szabo records information about the chick from the Mandy Lu nest. Photo: Ariel Zambelich/WIREDIt’s not always that simple, though. Sometimes mom and dad disagree about which chicks to feed. And, there are the rare exceptions in which parents have raised as many as three chicks at once. That’s not easy. Macaw parenting is intense and the amount of parental investment required is huge. It extends beyond the three-month period when the chicks are in the nest: Once fledged, chicks can stay near their parents for as long as a year, learning how to forage for food and defend themselves.

But none of that explains exactly what the macaws are doing, or why they’re pouring their resources into a chosen chick.

One possibility is that the strategy exists to combat sneaky egg dumping, in which birds stash their eggs in another’s nest, hoping their genes will benefit from someone else’s hard work. Researchers haven’t yet determined the frequency with which egg dumping occurs in macaws, but are hoping that genetic analyses will help them find out. George Olah, a graduate student at Australian National University, is extracting macaw DNA from feathers for genetic sequencing; Vigo will use those sequences to assess relatedness among both the local and larger macaw populations, hoping to identify any trends that might explain this somewhat surprising parenting system.

Hawkinson and Szabo are looking for trends, too. Each morning — unless it’s raining — they hike out into the jungle and (temporarily) retrieve chicks from the nests for data-collecting. Other project staff monitor nests and record the different kinds of behavioral interactions that take place among macaws living near the research center.

This includes things like hostile nest takeovers or the arrival of new nesting pairs.

Macaws are commonly described as partnering up for life, but Brightsmith thinks they’re more like some humans: serially monogamous. When their partners die, the birds will try and find another. He’s even seen a few instances of macaw “divorce.”

By far, the biggest threat to macaw nests are other macaws; predation on adult birds is exceedingly rare. Adults are big, their feet are strong, and their beaks can definitely do some damage (that’s why researchers greet the more ferocious nesting macaws with a big, stuffed glove at first, rather than an actual human hand). Macaws can be killed by monkeys, ocelots, and various predatory birds, like harpy eagles, but they can effectively avoid predation for decades.

Their strategies are simple and generally work well.

“Other than clay licks, they don’t ever touch the ground,” Brightsmith says. “The ground is too scary, too dangerous a place around here.” And macaws nearly always travel in pairs or family groups, and are always on the lookout for unwelcome visitors.

Twelve stories below Hawkinson, Szabo gives each of the two chicks a solution containing some dissolved salt. In addition to their work on macaw parenting, the scientists are testing a hypothesis describing why macaws and other parrots in the western Amazon supplement their otherwise vegetarian diets by eating clay [see box].

After finishing with the chicks, he sends them back up to Hawkinson. She replaces them in the nest, and descends from the tree. They pack up their gear and head back to the research center. It’s been an easy morning – only two nests to check – but it’s only the beginning of breeding season. Sixteen other nests have eggs; by the end of the season, that number should grow. Between now and April, each morning will see the scientists donning a pair of rubber boots and trekking off into the jungle, hoping to learn the secrets these macaw nests, and their weird-looking little chicks, hold.

Hawkinson heads into the rainforest to study another nest. All image by Ariel Zambelich

Hawkinson heads into the rainforest to study another nest. All image by Ariel Zambelich

Why Do Macaws Eat Clay?

At Tambopata, macaws and other parrots visit a clay lick just down the river. There, they politely pull footfuls of clay from an eroded cliff face. Then they fly to nearby trees and chew it slowly. Early studies suggested that clay-eating behavior arose as a way to remove the toxins (like tannins) contained in the plants the birds eat. But not everyone agrees. Brightsmith suspects the birds are using the reddish-brown muck to help augment a sodium-poor diet. His argument is multi-pronged. For starters, parrots all over the world eat all kinds of toxic stuff, including people-food. And the western Amazon basin — which is notoriously salt-poor — is the only place parrots visit clay licks. “I would say that 99.99 percent of all parrot individuals never eat soil,” Brightsmith said. So, the team is looking to see if supplementing chicks’ early diets with a saline solution leads to healthier chicks. If so, then maybe the team can finally put the toxin hypothesis to rest.On the rainforest floor, veterinarian Zoltan Szabo weighs and measures the odd-looking birds. At this point, they’re only two weeks old and don’t look anything like their rainbow-hued parents. Pink and sort of scaly, with patches of wiry fuzz and round, bulging bellies, the blind little birds look more like octogenarian dinosaur-chickens than the brilliantly colored adults they will become.