Goffin's cokatoo using a tool to get the desired treat. Image via Alice AuerspergMore than fifty years ago, humans were pretty well convinced that they were special, different from the rest of the animal kingdom. That all changed in 1964 when Jane Goodall reported her observations of tool use in chimpanzees. Now we have evidence that Goffin's cockatoos, parrots that don't use tools in the wild, have the cognitive capacity to learn to manufacture, modify, and use tools anyway.

Goffin's cokatoo using a tool to get the desired treat. Image via Alice AuerspergMore than fifty years ago, humans were pretty well convinced that they were special, different from the rest of the animal kingdom. That all changed in 1964 when Jane Goodall reported her observations of tool use in chimpanzees. Now we have evidence that Goffin's cockatoos, parrots that don't use tools in the wild, have the cognitive capacity to learn to manufacture, modify, and use tools anyway.

In the five decades since Jane Goodall first published her descriptions of chimpanzee tool use in the journal Nature, membership in the club of tool users expanded to include not just chimpanzees, but also elephants, dolphins, octopuses, crows, ravens, rooks, jays, dingoes, and dogs (sort of). Among birds, tool use is now well-documented in the corvids – that's crows, rooks, jays, ravens, and so on – but evidence has scant for tool use in other bird families. That all changed in 2012 when a captive male Goffin's cockatoo named Figaro figured out how to use sticks to get food from outside his aviary.

Figaro is one of a group of cockatoos housed at the Department of Cognitive Biology at the University of Vienna. As I wrote in Scientific American at the time, "one day, the male parrot dropped a pebble through an opening in the wire mesh surrounding the aviary in which he was housed, where it fell onto a wooden beam. Figaro tried in vain to retrieve the pebble with his claw. Frustrated, he flew away, retrieved a small piece of bamboo, and holding it in his beak, tried to use it to nudge the pebble back into his enclosure. He was unsuccessful. Still, no Goffin's cockatoo in the wild has ever been recorded using a tool, so the behavior was remarkable." Once researchers saw what he was doing, they decided to see how far is tool-related skills want. He eventually figured out how to use sticks to rake cashews into his aviary:

Not only could Figaro use small sticks that were lying around in order to get a snack, he also figured out how to manufacture tools, by using his beak to pry bits of wood off of the beams around his enclosure. In all, he manufactured ten different tools. And if that wasn't enough, he also learned to modify tools. One of the wood splinters he used proved too long to be useful, so he snapped it in half.

A Special Bird?

Figaro was a unique parrot for several reasons. First, his species doesn't use tools in the wild, so it's not an ability that's inherited. Unlike parrots, some corvids do use tools spontaneously. New Caledonian crows, for example, have an innate ability to make, modify, and use tools. All juveniles eventually acquire those skills, even if they're raised separately from adults who are already skilled tool users. They don't need to learn to do it. But Figaro's feats were the results of spontaneous insight rather than some kind of innate, pre-programmed behavior. Parrots also have curved beaks, rather than straight ones, making it much harder for them to manipulate tools the way that corvids do. Rather than constructing nests from bits of wood, as corvids do, they lay their eggs in pre-made cavities in trees. Parrots are simply not equipped with the most optimal set of anatomical or behavioral adaptations for acquiring tool use. And yet, Figaro figured it out.

Was Figaro particularly exceptional, or could most parrots learn tool use given the right conditions? That question led the researchers from Oxford University, the University of Vienna, and the Max Planck Institute to see whether their other cockatoos could learn tool use by watching Figaro. Led by Alice Auersperg, the researchers rounded up 12 other cockatoos, six male and sex female, and put them to the test.

Each of the 12 parrots was first put in front of a mesh box with a small cashew in the middle, along with a set of pre-manufactured tools, just to see whether any of them would try to use the tools on their own. None did. Then half of them – three males and three females – were allowed to observe Figaro retrieving the nut before trying it themselves. The other half saw "ghost demonstrations", in which (guided by invisible magnets), the tool appeared to move on its own to push the nut around, and then the nut (also guided by an invisible magnet) moved towards Figaro. By including the ghost demo as a control, the researchers could see whether the birds could learn tool use just by learning the mechanics of it, or whether it required a social component.

None of the birds who watched the ghost demonstrations ever learned how to use a stick to retrieve the food. That suggests that the transmission of tool use is an intrinsically social process.

Those who watched the social demonstration, on the other hand, all interacted with the pre-made tools quite a bit. However, only the three males ever managed to use them successfully to get their snacks. Dolittle and Pipin both picked up the skill after four demonstrations, while Kiwi started becoming successful after the fifth demonstration.

Further Innovations in Parrot Tool Use

What was striking, though, was that Dolittle, Pipin, and Kiwi each used a very different strategy than Figaro did. While Figaro always used the stick as a rake, the other parrots used it as a lever. That is, they kept the stick in contact with the ground and rotated it to bring the nut closer.

See examples of the two different strategies:

It turns out that the horizontal lever action may actually have been more efficient than Figaro's rake action. Figaro initially developed his method in the outdoor aviary, where he had to use the sticks to retrieve nuts from a bumpy wooden beam. In the current experiment, however, the nuts were placed on a smooth table, making the horizontal lever motion quite effective. Rather than blindly imitating Figaro's method, Dolittle, Pipin, and Kiwi instead identified the general principles behind his actions in order to achieve an identical goal. Rather than imitating his actions, they emulated his goal. That is itself quite cognitively sophisticated.

From Tool Use to Tool Design

Next, Auersperg wanted to see whether the parrots could use their new tool use skills and extend them tool manufacture. By that time, Pipin was starting to display reproductive behaviors and he couldn't be separated from his mate, so only Dolittle and Kiwi were given a chance. The set-up for the manufacture experiment was the same, but the birds weren't provided with any pre-made tools. Instead, they were given a piece of easily splintered wood. Dolittle learned to make tools on his own; Kiwi required just one demonstration from Figaro. Each bird successfully manufactured sticks ten different times.

Watch Dolittle and Kiwi manufacture tools:

Surprisingly, both Dolittle and Kiwi showed the impressive ability to use tools on other tools. Sometimes they lost their sticks behind the mesh. They would then manufacture a second tool, use it to retrieve the first tool, and then use that tool to get the food. In one trial, a total of seven subsequent tools were made before the nut was successfully eaten!

Both parrots also showed that they could modify tools, shaving off bits from the end, for example, if they couldn't fit through the holes in the mesh. Dolittle sometimes made tools that were too short to reach the cashew. After returning to the mesh, he discarded the tools as useless before even trying them. That, too, reflects an extraordinary amount of cognitive sophistication.

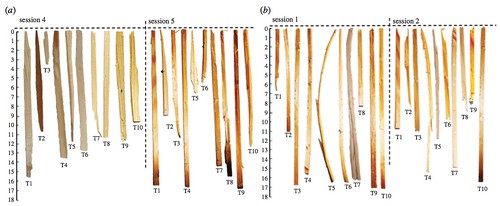

The tools made by Dolittle (a) and Kiwi (b). Image via Alice Auersperg

The tools made by Dolittle (a) and Kiwi (b). Image via Alice Auersperg

Cognitive Evolution

What do tool making parrots mean for our understanding of the evolution of cognition? First, that even just three additional cockatoos learned to make and use tools means that Figaro isn't a super-parrot. Rather, it means that Goffin's cockatoos possess the requisite cognitive machinery for tool-related abilities, but for whatever reason don't have the need to express it in the wild. That could be because they're foraging generalists – they'll eat just about anything – so they might simply never encounter a situation that requires tools. Add the impracticality of manipulating tools with any real precision given their curved beaks, and it stands to reason that there may simply be a mismatch between their underlying cognitive abilities and the ecological landscape in which they live.

Second, these findings underscore the difficulty in "unraveling individual or sex differences in innovative behaviour," according to the researchers. For example, it's unclear why a single individual (Figaro) spontaneously figured out how to make and use tools, while Pipin, Doolittle, and Kiwi only figured it out after watching a demonstration.

It is also not clear why all four cockatoo tool users are males, while none of the females figured it out. That could reflect the small number of individuals tested, it could reflect actual cognitive differences between the two sexes, or it could be that male and female cockatoos simply pay attention to different things when they find themselves in social encounters. That the demonstrator was male further confounds the issue. In the future, the researchers say, they will need to use female demonstrators as well.

Perhaps the most interesting question to fall out of the work with these parrots is whether there are differences between those species that have inherited tool-related adaptations, like New Caledonian crows, and those species that eventually acquire those abilities through individual or social innovation, like Goffin's cockatoos. Auersperg writes that this, in particular, is a "tantalizing but unresolved area for comparative cognition research."

Read the entire open-access paper for free at Proceedings of the Royal Society B.