Parrots of the Caribbean

Friday, July 31, 2009 at 11:22

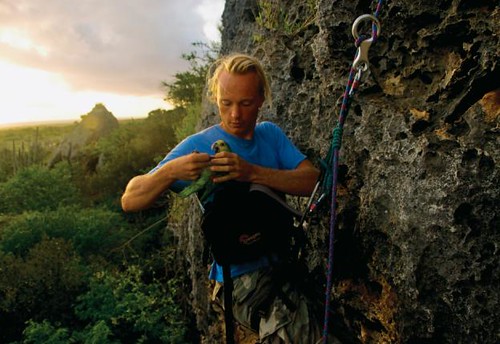

Friday, July 31, 2009 at 11:22  Rowan Martin gets ready to measure a yellow-shouldered parrot chick as part of an effort to protect the imperiled species. Photo: Kim HubbardIf you have heard of Bonaire at all, you may think of it as a haven for scuba divers or, maybe, loggerhead turtles. But this tiny island might also offer the best chance of survival for the yellow-shouldered Amazon parrot.

Rowan Martin gets ready to measure a yellow-shouldered parrot chick as part of an effort to protect the imperiled species. Photo: Kim HubbardIf you have heard of Bonaire at all, you may think of it as a haven for scuba divers or, maybe, loggerhead turtles. But this tiny island might also offer the best chance of survival for the yellow-shouldered Amazon parrot.

Dangling from the limestone cliff, Rowan Martin reaches into a hole in the sharp rock and retrieves a squawking bundle of green feathers. He slips it into a bag clipped around his waist and ascends his rope to a ledge, where research partner Sam Williams waits.

Science happens at dawn in the tropics. Beyond the cliff is a preposterously beautiful view. A plain of tall datu cacti gives way to crashing waves glowing with the first light from the east. But Martin and Williams, doctoral students from the University of Sheffield in England, are focused on their task: a variation on a checkup at the pediatrician’s office. The bundle is quiet as it is weighed inside a cloth sack suspended from a gram scale. As Martin records the number, Williams gently removes the young bird.

Peering at us with inquisitive gold eyes, the bird opens its sharp hooked beak. With surprising patience it allows Williams to run his thumb over the pale blue feathers on its forehead and blow aside neatly scalloping rows of green plumes highlighted by yellow patches on the shoulders and head, checking for mites. Rather than measuring the chick’s full height, it’s the length from shoulder to wingtip these researchers are after. Watching for signs of stress around the bird’s eyes, Williams fans the wing. The arc of feathers is vivid red, blue, and black.

Sam Williams and Rowan Martin track the parrot chicks, from egg to fledgling. Photo: Kim HubbardAudubon photography editor Kim Hubbard and I have arrived on Bonaire, an island in the Netherlands Antilles roughly 50 miles off the coast of Venezuela, during a crucial time for the island’s vulnerable yellow-shouldered Amazon parrots—the chicks are fledging. The IUCN’s Red List estimates the species as vulnerable and declining. The total number of these birds remaining in the world could be as low as 2,500, according to BirdLife International, the bird authority for the IUCN’s Red List. What seems certain within this species’ cramped range—northern coastal Venezuela to the islands of Margarita, La Blanquilla, and Bonaire—is that the roughly 650 parrots on Bonaire are potentially the most protectable population. Martin puts the situation in context. “In a population this small, the survival of every individual counts.” He adds, “In other places the problem is desperate. On Bonaire the problems seem solvable.”

Sam Williams and Rowan Martin track the parrot chicks, from egg to fledgling. Photo: Kim HubbardAudubon photography editor Kim Hubbard and I have arrived on Bonaire, an island in the Netherlands Antilles roughly 50 miles off the coast of Venezuela, during a crucial time for the island’s vulnerable yellow-shouldered Amazon parrots—the chicks are fledging. The IUCN’s Red List estimates the species as vulnerable and declining. The total number of these birds remaining in the world could be as low as 2,500, according to BirdLife International, the bird authority for the IUCN’s Red List. What seems certain within this species’ cramped range—northern coastal Venezuela to the islands of Margarita, La Blanquilla, and Bonaire—is that the roughly 650 parrots on Bonaire are potentially the most protectable population. Martin puts the situation in context. “In a population this small, the survival of every individual counts.” He adds, “In other places the problem is desperate. On Bonaire the problems seem solvable.”

The researchers are documenting key details of population dynamics for this long-lived, slow-breeding bird and are trying to make sure the basic science exists to create a conservation plan. Both men are athletic; the work demands it. Martin is lithe and pale blond, his face almost elfin. Williams is charismatic, always laughing, always moving—much like the parrots he has worked with since keeping birds as a boy. As with all science, their work builds on prior parrot research from around the globe, but they also make a particular effort to be sure they understand earlier conservation lessons learned on this little island.

Bonaire is arguably the best preserved of the roughly 30 principal Caribbean islands. It is known for some of the finest scuba diving in the hemisphere. With just 15,000 residents and roughly 75,000 overnight tourists annually (compared with 500,000 visitors to nearby Aruba), the island has a quiet, undeveloped feel. In 2010 Bonaire will become a sunny slice of Holland, its residents having voted to rejoin the island’s former colonial ruler as a special municipality. The change may give longstanding conservation projects a significant boost, including a push to generate all of Bonaire’s power needs on-island through wind and biodiesel.

While there are significant challenges to making a 24-mile-long sliver of desert in the Caribbean Sea fully sustainable, Bonaire has great potential as an ecotourism destination. Though the island is small, it offers tremendous natural variety: Mangroves abut cacti, and flamingo-filled salt flats lie within sight of some of the region’s most pristine coral reefs.

Large areas of the island and the surrounding waters are protected, which has allowed Bonaire’s sea turtle conservation program to become a model for other small islands. Though Bonaire has yet to be discovered for its birding, 214 species have been recorded here. Visitors can hunker down beside a watering hole to watch a parade of species from North and South America and the Caribbean. Or, if they’re intrepid, they can snorkel the mangroves and observe both marine and avian life up close.

Rising in the dark to the sound of the surf quickly becomes a ritual. As we head out to the research site this morning, there are no other vehicles on the road. Nightjars and iguanas abandon the pavement ahead of our truck. Cool air blows through the open windows. Williams disconcertingly assures us that the truck runs fine, most of the time, before mentioning that the undercarriage has an “intriguing” rattle. For three years Williams and Martin have been working themselves and their vehicle hard. We pass quickly through Bonaire’s two towns. Then, amid a landscape of barely visible desert scrublands, the pavement runs out and the intriguing rattle begins.

Many of the nests the scientists monitor are located inside Washington Slagbaai National Park, which covers most of the island’s northern fifth. Fernando Simal, the park’s manager, joins us to check these nests. Williams points out red-necked pigeons and tropical mockingbirds, calling for “arms in” as we barrel through a gauntlet of overgrown mesquite. He explains that this year’s parrot chicks are almost through their own gauntlet. “We started with 62, but we only had 29 reach this point,” he says. Introduced predators take a toll, but the chicks that do fledge have a good chance of living 20 to 30 years.

As the crimson Toyota Hilux bounces along a dirt track in golden light that suffuses the rolling hills, Williams points to a dividivi tree ahead where they’ve been monitoring a parrot chick. Yellow-shouldered Amazons, like all but one of the world’s nearly 350 species of parrots, do not build nests. They rely on finding cavities in trees and rock faces. This means that once a good hole is found parrots will return to the spot year after year. “This chick is eight weeks old,” Williams says. He laughs at himself, almost shyly, saying, “That’s the way parents talk about their kids.” But as we stop he can’t resist adding, “I could tell you to the day if you like.”

Williams and Simal approach the tree, preparing to record the last set of growth measurements before the chick fledges, but a piece of the tree has been broken away. There are downy feathers scraped onto the bark. The nest hole is empty. The first reaction is disbelief. Then disgust. Williams’s face flashes through the impact of so much hope and effort gone for naught.

“Poached!” moans Simal.

This makes seven out of 29 chicks this year that have been taken from their nests to be sold as pets. Williams’s hurt bursts for a moment into anger. “If I ever caught one of these poachers, I’d break his legs,” he says. While it is a fleeting impulse that he wouldn’t act on, it does reflect the depth of his feelings for the birds. “If they took an egg, it’s really not a big deal. But when nothing else is going to kill it. . . . At this point, the only thing it has to do is fledge. . . . I had known the chick since it was an egg.”

Martin, meanwhile, has been checking other nests. His reaction to the news is more measured. “The single best thing that could happen would be to catch a poacher in the act, have him prosecuted, and his picture in the paper,” he says.

Although there have been laws protecting the parrots on Bonaire since 1952, they simply haven’t been enforced. Meanwhile, yellow-shouldered parrots have gone extinct on Aruba. The birds live in an arid habitat, which in this part of the world means they are native to just three other islands and a few disconnected dry patches of coastal Venezuela.

The populations are isolated from one another, and current conditions on the mainland make conservation there dangerous and difficult, if not impossible. Mainland poachers could take as many as 70 percent of the chicks. Even though there are thought to be more yellow-shouldered parrots on the Venezuelan island of Margarita, poaching there, at least in some places, may claim as many as 90 percent of the chicks, leaving Bonaire as probably the species’ best chance.

Waiting one morning for the parrots at a nest site, we spot four ruby topaz and two emerald hummingbirds among white blossoms. For a quarter of an hour we watch the darting shards of color turn the branches into a kaleidoscope. Unexpected sightings are regular occurrences on Bonaire. With so little real estate, habitats overlap so that in one direction there could be a crested caracara in a tree alongside an iguana, while in the other direction there might be a Caribbean coot, a brown booby, or a blue-tailed skink.

When several parakeets fly past, Williams points out how they flap from the shoulder as compared to parrots, which fly like ducks—he extends his arms straight out and frantically flaps just his hands to demonstrate. The bushes rattle with lizards and the air is full of bird calls, so we never quite have his complete attention. Williams’s ears seem to have control of his head, causing it to constantly bobble about in search of a better fix on the soundscape. He interrupts himself midsentence with, “That’s the bananaquit. Hear how it seems to have a lisp?” Or, “That squeaky-dog-toy sound is the flycatcher.”

Even in such a peaceful spot there are reminders of what is at stake. Sun-bleached pieces of a makeshift ladder have been left by poachers. At other sites the researchers have found ropes hanging down cliffs. In many ways it is a competition between the conservationists and the poachers.

Buchie Frans, 79, a poacher, is helping young bird scientists with their conservation efforts. Photo: Kim HubbardBuchie frans greets Sam Williams with a shout, then chastises him for having waited so long to visit. Williams excitedly introduces us to this Bonairean for whom he has enormous affection and respect despite the fact that he’s a poacher.

Buchie Frans, 79, a poacher, is helping young bird scientists with their conservation efforts. Photo: Kim HubbardBuchie frans greets Sam Williams with a shout, then chastises him for having waited so long to visit. Williams excitedly introduces us to this Bonairean for whom he has enormous affection and respect despite the fact that he’s a poacher.

Collecting birds was something Frans learned as a boy from his father. He says it was done in a way that took sustainability into consideration—never taking chicks from the same nest in successive years. Frans says he is about to turn 80, but the tattoos on his arms bounce as his muscles bulge with every gesture. He says he stopped poaching in 2002, when the fine was raised to roughly $600, and he is disdainful of the current poachers who resort to chainsaws to get chicks out. “People are stupid. You chop it. That’s the last time. You can’t take birds there anymore.”

With us is Adolphe Debrot, a scientist who directs the CARMABI Foundation, one of the main environmental organizations for the Netherlands Antilles, who is visiting from Curacao for the day. His decades of experience have sustained his respect for island traditions and for pragmatism. “I’m sure all the poachers on the island are known,” he says to Frans. “Give them a lesson on how to poach. If you are going to do something, do it right.”

Frans, who has been vibrant and confident to this point, deflates for a moment. “They don’t listen. You can’t teach them.” Debrot lets it go but hopes he has planted an idea.

There are islanders who, because they see the parrots regularly, have a hard time believing they are endangered. The birds are attracted to town because they love the mangoes and kenepa fruits introduced to Bonaire in backyard gardens. The parrots often feed in loud flocks. They are messy, wasteful eaters. When a parrot discards a mango after a single bite, it does not endear the birds to the islanders, except as highly prized pets.

James Gilardi, director of the World Parrot Trust, says this loathe-and-love phenomenon is found wherever parrots are. “It is sometimes possible to educate your way out of this situation. The most successful protection programs combine enforcement of anti-poaching laws and the recruitment of poachers to act as protectors.”

In 2002 all pet parrots on the island were banded without penalty, but to discourage poaching, the fine for possessing an unbanded bird was raised. For islanders who rarely get anything better paying than a service job, the $600 penalty could be more than two weeks’ wages. Poachers are thought to sell the chicks for $150 apiece.

George “Cultura” Thondé, chief ranger at Washington Slagbaai National Park. Photo: Kim HubbardGeorge Thodé, chief ranger at the national park, saw the increased fine as a heavy-handed approach and feared it would create animosity toward the parrots. “I had to go on the radio to ask forgiveness on behalf of the bird.” To a similar end, Martin and Williams have adopted a playful strategy—they dressed as parrots to march in the Bonaire Day parade, and they write the “Dear Olivia” column for the local newspaper in the voice of a cheeky, advice-giving parrot.

George “Cultura” Thondé, chief ranger at Washington Slagbaai National Park. Photo: Kim HubbardGeorge Thodé, chief ranger at the national park, saw the increased fine as a heavy-handed approach and feared it would create animosity toward the parrots. “I had to go on the radio to ask forgiveness on behalf of the bird.” To a similar end, Martin and Williams have adopted a playful strategy—they dressed as parrots to march in the Bonaire Day parade, and they write the “Dear Olivia” column for the local newspaper in the voice of a cheeky, advice-giving parrot.

Their aim is to duplicate the success of Bonaire’s sea turtle protection effort, which began in 1991 and has preserved and expanded the foraging and nesting habitat of hawksbill, green, and loggerhead turtles. But perhaps most important, it changed the local perception of the island’s sea turtles. Turtle soup used to be a common Sunday dinner, and turtle shells were sold in tourist shops. Education and enforcement of conservation laws have all but ended the poaching.

Another lever may be economics. Almost all Bonaireans earn their livings, directly or indirectly, through tourism. To this point, that has largely meant visiting scuba divers, so protecting water species makes sense to islanders. But if tourists begin to come for the land animals as well, that might change.

There are extraordinary birding opportunities on Bonaire. A road ribbons around the island’s low southern end, where nothing more than a latticework of coral barrier beaches separates land from sea. Levees have been used to turn natural saltwater lagoons into a solar salt works. The concentration of brine shrimp turns the most saline pools a bright pink. Within the salt works, hidden from public access, is a sanctuary with 5,000 flamingos, an important breeding population for these shy birds.

Washington Slagbaai Park has natural saliñas, or saltwater lagoons, which also attract flamingos, though in smaller numbers. One night we enter the national park to watch the flamingos feeding at dusk. They are skittish around people, but we’re able to inch our way closer using our vehicle as a blind. Moving through shallow pools, the flamingos look like limber punctuation: shifting commas and question marks. In the distance there is the sound of ocean surf; nearby, grunting, gooselike calls pass back and forth among the flamingos as they worry the sand with their bills, filter-feeding on mollusks, brine shrimp, and brine flies.

On other parts of the island, Bonaire’s unusual confluence of birds is on display. Next to a waterhole anything is possible. There could be yellow warblers, troupiols, and scaly-naped pigeons, or white-tipped doves, pearly-eye thrashers, and Caribbean elaenias.

One morning we join a tour kayaking the mangrove forest of Lac Bay. Deep among the slow-moving channels, we clamber out of our kayaks, wearing snorkel and mask, and swim slowly into a narrow tunnel entirely enclosed by the tree canopy.

Oysters so thin they become translucent in sunlight live in clutches along the waterline. Dropping below the surface, the color scheme changes from earth tones to Technicolor. There are bright anemones and brilliant coral on the mangrove roots. An upside-down jellyfish pulses past; its stubby tentacles face skyward so that the algae living among them can photosynthesize. Our guide points to a scorpion fish settled on the bottom—an object lesson in keeping our feet afloat. The camouflaged fish is benign unless we step on its venomous spines. We drift by young barracudas and red snappers as well as porcupine fish and needlefish.

Looking up, I notice a green heron just six feet away. It seems aware of us but apparently unconcerned. Though we aren’t given time to linger, I’m sure a more concerted amphibian approach to birding would be rewarded.

The bananaquit is known in Dutch as suikerdiefje, or “sugar thief.” Photo: Kim Hubbard

The bananaquit is known in Dutch as suikerdiefje, or “sugar thief.” Photo: Kim Hubbard

When we visit the office of Sea Turtle Conservation Bonaire, the group credited with protecting the island’s turtles, Mabel Nava, the director, remarks on our serendipitous timing. Because nests are so closely monitored, she is able to invite us to Klein Bonaire, a small uninhabited island a half-mile off the coast, for the anticipated hatching of a loggerhead nest that night.

With the sun quickly dropping, we arrive just in time to see a volcano of tiny turtles erupting from the sand. Eggs are buried deep enough that no single hatchling could dig its way out, but collectively they rise through the sand in a living ladder. It is an extraordinarily affecting experience to watch each palm-size turtle blink away the sand and begin crawling with great urgency.

Word has spread about the event, and a series of small boats have arrived. About 30 people, mostly expatriates though a few native islanders, form a sort of red-carpet phalanx cheering the turtles toward the water. Children scramble to reorient inland-wandering hatchlings. The mood is joyous. Soon the water is polka-dotted with tiny turtle heads. They are bound for the sea, where they live for between five and ten years before beginning the migratory life of adult sea turtles. All told, there are 149 dramatic launches. But only an estimated one in 1,000 turtles reaches adulthood.

With survival odds like those faced by the turtles or the parrots, Williams and Martin see both Bonaire and the parrots teetering on an excruciating balancing point, but the people working on environmental issues there give them hope. “It is hard not to be cautiously optimistic for the future,” Martin says. “The parrot is very much a part of Bonaire.” And as the success with turtles has shown, the islanders are very capable of transforming perceptions to save one of their own.