A talkative bird gone without a word

Tuesday, August 28, 2012 at 23:41

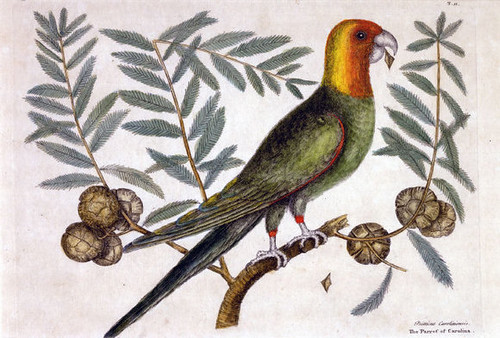

Tuesday, August 28, 2012 at 23:41  Mark Catesby's illustration of the parakeet. It's from Catesby's Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, which was published in several editions in the mid 1700s. Courtesy of Wilson LibraryThe Carolina parakeet, a small, gregarious parrot with a vibrant green, yellow and blood-orange plumage, once flitted and chattered widely through the state’s forests and lowland swamps.

Mark Catesby's illustration of the parakeet. It's from Catesby's Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, which was published in several editions in the mid 1700s. Courtesy of Wilson LibraryThe Carolina parakeet, a small, gregarious parrot with a vibrant green, yellow and blood-orange plumage, once flitted and chattered widely through the state’s forests and lowland swamps.

Then about a century ago, it vanished, leaving an old-fashioned mystery for modern ornithologists.

But the Carolina Parakeet has appeared again this summer — in prints, photographs and paintings — on display in the North Carolina Collection Gallery at Wilson Library on the UNC-Chapel Hill campus through Sept. 30.

On Wednesday, Aug. 29, at 5:15 p.m., there will be a viewing of the exhibit and a talk 30 minutes later by two ornithology experts from the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences — John Gerwin, the curator of ornithology, and Brian O’Shea, the collections manager for ornithology.

John James Audubon's illustration of the North Carolina Parakeet. Courtesy of Wilson LibraryNo one knows for sure what happened to America’s lost parrot.

John James Audubon's illustration of the North Carolina Parakeet. Courtesy of Wilson LibraryNo one knows for sure what happened to America’s lost parrot.

Milliners hunted them for their fashionable feathers.

Trappers caught the verbose birds to sell as caged pets.

Farmers shot the parakeet flocks as menaces to their corn crops and fruit orchards.

And European honeybees, which traveled in swarms and built elaborate nests in the same hollow trees where the birds roosted, brought new competition in a habitat that extended south to the Gulf of Mexico, east to the Ohio Valley and as far north as New York and Wisconsin.

Though no one knows the exact date the bird became extinct, the last reported killing of the wild specimen was in 1904 in Okeechobee County in south-central Florida.

In 1917 and 1918, the last two known Carolina parakeets died in captivity in the Cincinnati Zoo. The pair, named Lady Jane and Incas, lived together for 32 years. Lady Jane died in 1917, and Incas, her mate, went within a year on Feb. 21, 1918. Their demise coincided with the extinction of another iconic bird, the North American passenger pigeon. The last of the breed, a captive bird named Martha, died in 1914, also at the Cincinnati Zoo.

Ornithologists are fascinated by the parakeet, also known as the Carolina Parrot, for more than its mysterious disappearance. They are curious about its adaptation to colder climes atypical of the rain forests and tropical climates where most parakeet species thrive today.

The ornithologists and scientists interested in the extinct bird pore over journals from 18th- and 19th-century explorers who documented their findings and sightings. They turn to the colorful and detailed illustrations of John James Audubon, the 19th-century naturalist and painter whose color-plate book, “The Birds of America” offers a vivid picture of bygone eras.

One rare 1906 photo of Paul Bartsch, a Smithsonian scientist, offers a true-to-form, grainy, black-and-white image of Doodles, his pet Carolina Parakeet, perched on his tie knot.

Hundreds of skins and 16 skeletons are housed in museums around the world. Egg specimens collected and sold to museums when the parakeet was becoming an endangered species offer a wealth of molecular study materials.

Audobon noted in one of his journals that cats died from eating Carolina Parakeets, leaving some to wonder whether the bird, which ate the toxic seeds of cockleburs, might have been poisonous.

The bird lived in forests along rivers and flocked to swampland cypresses, using large, hollow trees as roosting and nesting sites.

In the 1800s, they became a popular target for hunters, according to documentarians, because their colorful feathers were in high demand as accessories for ladies’ hats.

Though some of the parakeets, or small parrots, were shot for food, farmers began shooting them in great numbers because they would flock together in cornfields, orchards and garden flocks and devastate their cash crops.

The birds, Gerwin said, had a bad habit that made them easy marks and almost certainly led to their quicker demise.

“The poor bird had a bad behavioral trait,” Gerwin said. “They were very social, and when one was shot they would fly away and then return immediately to where the injured or killed bird was.”

Another threat to the species, Gerwin speculated, was the growth boom of the 1800s that led to massive deforestation.

“We think it’s a problem now,” Gerwin said, “but it was even worse in the 1800s.”

People continue to hold out hope that not only will the mystery of the parakeet’s extinction be solved, but that it might also be proved untrue by the discovery of Carolina Parakeets in some forest faraway.