Hybrids and the future of Aviculture

Wednesday, April 17, 2013 at 3:57

Wednesday, April 17, 2013 at 3:57  Hotly debated, hybrid parrots might be the future for aviculture. Few issues are more hotly debated in modern-day aviculture than crossbreeding or hybridisation of different parrot species. Whenever someone brings up hybrids immediately people stand up to solemnly declare they are against it. It is the avicultural form of political correctness. A responsible parrot breeder is against hybridisation and that’s the end of it. Recent debates on facebook and grim burns of people giving an inkling of taking an interest in hybrids encouraged me to have a closer look at this issue.

Hotly debated, hybrid parrots might be the future for aviculture. Few issues are more hotly debated in modern-day aviculture than crossbreeding or hybridisation of different parrot species. Whenever someone brings up hybrids immediately people stand up to solemnly declare they are against it. It is the avicultural form of political correctness. A responsible parrot breeder is against hybridisation and that’s the end of it. Recent debates on facebook and grim burns of people giving an inkling of taking an interest in hybrids encouraged me to have a closer look at this issue.

Gene pool

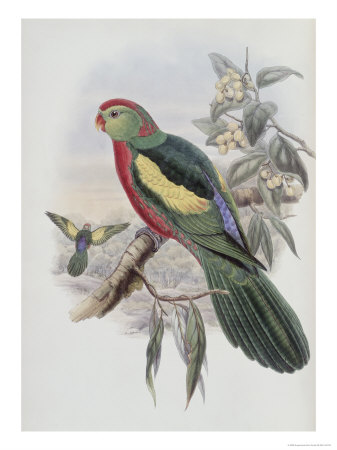

Unnatural? John Gould described the natural occurring hybrid of Australian King parrot and Red-winged Parrot as a seperate species: The Beautiful King-Parrot (Aprosmictus insignissimus). One of many such natrual hybrids that have caused confusion in ornithology.Opposition to breeding hybrids boils down to a few arguments. Hybridisation is perceived as something unnatural. Most often expressed in the argument of our responsibility to keep the gene pool pure. Sometimes augmented with a desire to conserve or maintain a species in captivity usually followed by how the natural world is being destroyed and captive breeding is the best that can happen for such a species.

Unnatural? John Gould described the natural occurring hybrid of Australian King parrot and Red-winged Parrot as a seperate species: The Beautiful King-Parrot (Aprosmictus insignissimus). One of many such natrual hybrids that have caused confusion in ornithology.Opposition to breeding hybrids boils down to a few arguments. Hybridisation is perceived as something unnatural. Most often expressed in the argument of our responsibility to keep the gene pool pure. Sometimes augmented with a desire to conserve or maintain a species in captivity usually followed by how the natural world is being destroyed and captive breeding is the best that can happen for such a species.

Once I was a firm believer of these dogmas and actually held the chair of captive breeding coordinator at a national avicultural parrot conservation organisation. At the time I was at university studying biology and did the obligatory courses on evolutionary genetics and on species concept. My views changed quite a bit.

Let’s take a look at that gene pool. As it is represented in the argument above it is an entity that somehow represent the essence of a species, a singular entity that makes a species a species.

Australian lorikeets regularly hybridise. Image by Tainia Finlay

Australian lorikeets regularly hybridise. Image by Tainia Finlay

Nature of genetic differences

In biological terms however the gene pool is more fluent, a term that describes the total diversity of genes in a given population. Gene pools for instance overlap. 97% of the genetic code of Chimpanzees and the human species for example is the same. Few of those code differences actually lead to observable phenotypic differences as they are synonymous substitutions. So what makes chimps different from people is just a tiny bit of that 3% difference in genetic code, just trace amounts of the overall gene pool. A hybridisation event between humans and chimp, were they fertile, would leave very little genetic trace after a couple of generations of backcrosses

Relations between parrots, especially among many of the South American groups are even more tight then those of people and apes. Because their limited genetic distance a moderate amount of hybridisation between these species with sufficient back-crossing would make little or no impact on the genetic make-up of the species.

Hybrids in speciation

Free-range hybrid macaws in love. Species are often defined as “a population of actually or potentially interbreeding individuals that produce fertile offspring". However hybrid zones are a common phenomenon in birds. They occur where two related species distributions meet (see this example of the Crimson Rosella complex 1, 2). In the definition above the interbreeding species should be regarded as a single species. But the two forms do not normally merge into one. In the study of hybrid zones species are therefore often defined as “taxa that retain their identity despite gene flow” emphasising the different adapted phenotypes on either side of the hybrid zone instead of genetic isolation.

Free-range hybrid macaws in love. Species are often defined as “a population of actually or potentially interbreeding individuals that produce fertile offspring". However hybrid zones are a common phenomenon in birds. They occur where two related species distributions meet (see this example of the Crimson Rosella complex 1, 2). In the definition above the interbreeding species should be regarded as a single species. But the two forms do not normally merge into one. In the study of hybrid zones species are therefore often defined as “taxa that retain their identity despite gene flow” emphasising the different adapted phenotypes on either side of the hybrid zone instead of genetic isolation.

Nature has many ways to evolve species. Genetic integration plays a variety of roles. Purity of a gene pool is without meaning. There never was a perfect creation for which we now bare responsibility. Nature is organised differently or perhaps is just not that organised. Emphasis on purity is a throwback to the age of eugenics.

Hybrid vigour

Hybrid vigour? This Corella/Galah hybrid, from a flock of 7 of these birds in Perth, certainly has no trouble surviving in the wild. Image by Graham R. There are two opposing concepts associated with hybrids: outbreeding depression and hybrid vigour. Outbreeding depression describes how the break up of co-adapted gene complexes leads to less fitness in hybrid progeny. Hybrid vigour on the other hand describes how the increased heterozygosity that results from hybridisation benefits the individual often resulting in bigger, stronger and longer lived animals. Mules are an example of both. Mules are stronger then either horses or donkeys with a temperament that makes them highly valued. Mules are however infertile which reduces their biological fitness to zero. Hybrid vigour seems the more common result when parrots crossbreed. But there are also examples of outbreeding depression, usually when the species are more distantly related and have incompatible ecological adaptations. The bigger size and better general health of most of the commonly available hybrid parrots is something to keep in mind when buying a companion parrot.

Hybrid vigour? This Corella/Galah hybrid, from a flock of 7 of these birds in Perth, certainly has no trouble surviving in the wild. Image by Graham R. There are two opposing concepts associated with hybrids: outbreeding depression and hybrid vigour. Outbreeding depression describes how the break up of co-adapted gene complexes leads to less fitness in hybrid progeny. Hybrid vigour on the other hand describes how the increased heterozygosity that results from hybridisation benefits the individual often resulting in bigger, stronger and longer lived animals. Mules are an example of both. Mules are stronger then either horses or donkeys with a temperament that makes them highly valued. Mules are however infertile which reduces their biological fitness to zero. Hybrid vigour seems the more common result when parrots crossbreed. But there are also examples of outbreeding depression, usually when the species are more distantly related and have incompatible ecological adaptations. The bigger size and better general health of most of the commonly available hybrid parrots is something to keep in mind when buying a companion parrot.

Hybridisation and conservation

Hybrid vigour has practical uses for conservation. Island species usually result from just a few ancestors, the founders, which made it to the isolated landmass. The resulting population has little genetic variation. This means that such populations have a compromised ability to fight new diseases to which they get exposed to in the modern world. The Echo parakeets struggle with PBFD is an example of this.

Parakeet phenotypes. Clockwise from top left: Forbes’, ‘slight hybrid’, ‘distinct hybrid’, red-crowned.On the Chatham Islands the endemic Forbes' parakeet Cyanoramphus forbesi hybridises with the introduced red-crowned parakeet C. novaezelandiae. Measures of the immune function, not surprisingly, were found to be markedly higher in the more cosmopolitan red-crowned parakeet than in the island endemic Forbes' parakeet. The 2006 study however also found that back-crosses that mostly resembled the Forbes' parakeet in phenotype, retained much of the immune function of the red-crowned parakeet. In the discussion the research team suggests that modest hybridisation could help those endangered species that experience immune problems to obtain the genes they need to fight disease. Fertility problems in severely inbred populations like Spix macaws for example could be addressed in the same way.

Parakeet phenotypes. Clockwise from top left: Forbes’, ‘slight hybrid’, ‘distinct hybrid’, red-crowned.On the Chatham Islands the endemic Forbes' parakeet Cyanoramphus forbesi hybridises with the introduced red-crowned parakeet C. novaezelandiae. Measures of the immune function, not surprisingly, were found to be markedly higher in the more cosmopolitan red-crowned parakeet than in the island endemic Forbes' parakeet. The 2006 study however also found that back-crosses that mostly resembled the Forbes' parakeet in phenotype, retained much of the immune function of the red-crowned parakeet. In the discussion the research team suggests that modest hybridisation could help those endangered species that experience immune problems to obtain the genes they need to fight disease. Fertility problems in severely inbred populations like Spix macaws for example could be addressed in the same way.

Breeding for conservation?

Are aviculturist actually preserving species? From conservation breeding science we know that to maintain most of the genetic material in a captive setting we need about 500 founders. That is 500 random birds from the original population contributing their offspring to the breeding program. This will preserve about 90% of the total genetic diversity of the original population.

The reality of aviculture however is that few, if any parrot species in aviculture can boasts having 500 founders and those that have certainly where not selected randomly.

How many Yellow-headed amazon parrots actualy contributed to the present day captive breeding population?Selection

How many Yellow-headed amazon parrots actualy contributed to the present day captive breeding population?Selection

Aviculture is hugely selective. The birds that came to our care in aviculture went to a process of capture and transport. The most stress sensitive birds did not make it trough that process and their genes never made it to aviculture. These were the birds that perhaps were the most wary about predators or were good at avoiding fights with their congeners. The birds in aviculture now have fewer of those genes and if this population was ever used for reintroduction the birds in this stock might spend too much time conducting maladaptive behaviours like fighting instead of looking out for predators. From this genetic bottleneck alone captive bred populations could become unsuitable for reintroduction.

The future of all parrot breeds in captivity can be seen in the humble budgie. After many generations in captivity they hardly compare to their wild counterparts. Image by PuppiesAreProzac.What comes next however is even more detrimental. We have seen that the birds that survived the wild bird trade do not represent the wild population as a whole. But with breeding animals in captivity there is more selection. For starters not all wild caught birds will breed in captivity. If one reads the standard works of early aviculture you will find it crammed with failures and resorting to artificial measures, like incubators and hand-rearing, to get birds to reproduce.

The future of all parrot breeds in captivity can be seen in the humble budgie. After many generations in captivity they hardly compare to their wild counterparts. Image by PuppiesAreProzac.What comes next however is even more detrimental. We have seen that the birds that survived the wild bird trade do not represent the wild population as a whole. But with breeding animals in captivity there is more selection. For starters not all wild caught birds will breed in captivity. If one reads the standard works of early aviculture you will find it crammed with failures and resorting to artificial measures, like incubators and hand-rearing, to get birds to reproduce.

Birds that experience a lot of stress in captivity will not breed, stress hormones directly reduce fertility. The more docile birds with little fear of people have a distinct advantage in a captive situation, propagating this trait over the generations.

Genetic footprint

In captive breeding projects, aimed at conservation and reintroduction, care is taken that not one individual can get a disproportional share of progeny into the next generation over others. Their genetic footprint in the next generation should be equal to that in the founding population. In aviculture however the most prolific birds determine the future gene pool.

Clutch size is a good example for this phenomenon. Lets say that macaws in the wild have a clutch of 2 eggs. This ensures they are able to raise enough offspring and not starve themselves while caring for their progeny. Laying a clutch of 3 eggs is only adaptive under exceptionally circumstances and therefore a rare trait in the macaw population. However in captivity there are no restrains on food availability. A clutch of 3 eggs is just as likely to reach maturity as a clutch of 2. But birds with the 2 eggs clutch trait has fewer representatives in the next generation then the birds with the 3 egg clutch size. The rare maladaptive trait has increased in the gene-pool and the adaptive trait has lost genetic footprint. If this is not corrected by removing some birds from the breeding population, then the 3 egg clutch size trait will rapidly become the norm over the generations.

Domestication

These genetic changes that captivity induces together describe domestication. The captive environment is a selective environment and favours traits that are maladaptive in the wild and more importantly diverges captive populations from their wild counterparts. Captive breeding programs for conservation correct for domestication processes by keeping the generations in captivity as few as possible.

Hybrids often occour in introduced parrot populations. This hybrid in Wiesbaden stems from one pair of wild caught but escaped Blue fronted and Orange winged amazons.Domestication occurs rapidly and the effects on the organism are profound. I study urban parrots. The numerous city parrot populations in North America and Europe are all introduced. They stem from birds that fled captivity. All of these populations stem from a time when wild caught imports of parrots was still the norm and captive breeding was the exception. Budgerigars and cockatiels are some of the most prolific and widely kept pets in the world and many escapees are recorded. Their country of origin however rapidly ended its trade in wild-caught birds and although Australia has many parrots that live in urban areas, no population of Australian parrots established outside of Australia. Budgerigars had a go in Florida but that population is set for expiration. Birds that are bred in captivity apparently loose their ability to survive in the wild very rapidly.

Hybrids often occour in introduced parrot populations. This hybrid in Wiesbaden stems from one pair of wild caught but escaped Blue fronted and Orange winged amazons.Domestication occurs rapidly and the effects on the organism are profound. I study urban parrots. The numerous city parrot populations in North America and Europe are all introduced. They stem from birds that fled captivity. All of these populations stem from a time when wild caught imports of parrots was still the norm and captive breeding was the exception. Budgerigars and cockatiels are some of the most prolific and widely kept pets in the world and many escapees are recorded. Their country of origin however rapidly ended its trade in wild-caught birds and although Australia has many parrots that live in urban areas, no population of Australian parrots established outside of Australia. Budgerigars had a go in Florida but that population is set for expiration. Birds that are bred in captivity apparently loose their ability to survive in the wild very rapidly.

Domestication as the new focus for aviculture

Checks and balances to prevent domestication in conservation breeding projects are in place. Private aviculture however largely lacks such measures. Ties with our parrots’ natural counterparts have been severed and will never be mend. Is everything lost now?

Aviculturists are not preserving species, they practice bird domestication and perhaps that is what they should do? Could aviculture prepare birds for a future in the companion of people? When parrot populations in the care of aviculturist are set for domestication can we make it a good thing?

The time parrots take to approach a new toy has been taken as measure of neophobia and has been shown to contain a considerable genetic component with some familie-lines showing less neophobia then others. Image by Bram CymetSelective breeding could rid our captive parrot population from some the anxieties that accompany their lives. Great strides in heritable tameness can be achieved in only 10 generations as has been shown in a fox domestication project in Russia. Perhaps aviculturist could select against neophobia and decrease this trait that presently plagues so many birds in captivity. Another issue with parrots in captivity is feather picking. This trait has also been shown to posses a considerable genetic component that can be selected against.

The time parrots take to approach a new toy has been taken as measure of neophobia and has been shown to contain a considerable genetic component with some familie-lines showing less neophobia then others. Image by Bram CymetSelective breeding could rid our captive parrot population from some the anxieties that accompany their lives. Great strides in heritable tameness can be achieved in only 10 generations as has been shown in a fox domestication project in Russia. Perhaps aviculturist could select against neophobia and decrease this trait that presently plagues so many birds in captivity. Another issue with parrots in captivity is feather picking. This trait has also been shown to posses a considerable genetic component that can be selected against.

Feather picking has been shown to carry a gentic component. Breeding parrots that pick their feathers is therefor inadvisable.Certainly this type of selective breeding would indeed be noble and better the reputation of aviculture, something breeders of hybrids are often accused of harming. More importantly it will increase the quality of live for the birds in our care. Surly this could be as fulfilling as avicultures’ present day focus on perpetuating colour mutations.

Feather picking has been shown to carry a gentic component. Breeding parrots that pick their feathers is therefor inadvisable.Certainly this type of selective breeding would indeed be noble and better the reputation of aviculture, something breeders of hybrids are often accused of harming. More importantly it will increase the quality of live for the birds in our care. Surly this could be as fulfilling as avicultures’ present day focus on perpetuating colour mutations.

Present day aviculture seems to be stuck at the dog equivalent phase of taming wolves when the future actually lies with Alsatians, Golden retrievers, Newfoundlanders and so on. We no longer care if our dogs descents from the Eurasian or Indian wolf or a mix of those. We select our pets differently. This is the unavoidable future for the parrots in our care. Future parrot generations in aviculture will be selected for their beauty, their ease with live in captivity and their trainability.

Macaw hybrid distroying a leaflet that says that parrot behavioural problems can be fixed. Indeed they can and selectively breeding hybrids for the traits we value in companion parrots is one way forward.Personally I do not care much for the colours of hybrid macaws. Others evidently do. What I find more intriguing are the reports of these hybrids possessing a more balanced personality. Combined with the benefits of hybrid vigour it are these traits in which breeding hybrids really finds its merit. Combining different species characters to eventually form a true domestic parrot.

Macaw hybrid distroying a leaflet that says that parrot behavioural problems can be fixed. Indeed they can and selectively breeding hybrids for the traits we value in companion parrots is one way forward.Personally I do not care much for the colours of hybrid macaws. Others evidently do. What I find more intriguing are the reports of these hybrids possessing a more balanced personality. Combined with the benefits of hybrid vigour it are these traits in which breeding hybrids really finds its merit. Combining different species characters to eventually form a true domestic parrot.

Would I pay more for such a parrot? I certainly would if I was looking for the perfect parrot companion. As much as I hate to talk about parrots as a product, hybrid parrots just might be what the companion parrot market demands as it is the better product for their needs.